In his doctoral dissertation No Sure Victory: Measuring US Army Effectiveness and Progress in the Vietnam War, Gregory A. Daddis, Lieutenant Colonel, United States Army, reserves a section about the Ia Drang battle (from page 124 to page 135), in which he discussed about the combat effectiveness of US 1st Air Cavalry Division. He writes (page 133):

By using new airmobile techniques, the 1st Cavalry seemed to achieve victory in the Ia Drang using standard, conventional operations. Moore had attacked and defended, terms that any World War II or Korean War veteran could comprehend.

Daddis’ fundamental error lies in asserting that the victory was achieved at Ia Drang by “1st Cavalry” and by “using new airmobile techniques”. It was achieved by the US Air Force and by using the Arc Light strategic bombing. To the contrary of the general understanding of the US military establishment, the US military historians and scholars, the main trust at Ia Drang was the five-day B-52 airstrike operation and the secondary trust was the Long Reach operation that 1st Cavalry conducted in three phases – All the Way of 1st Air Cav Brigade, Silver Bayonet I of 3rd Air Cav Brigade and Silver Bayonet II of 2nd Air Cav Brigade. Daddis fails to grasp the operational concept of the “Pleiku Campaign” (the correct name is Long Reach or Pleime-Chupong campaign), which consists of using B-52 airstrikes with the support of 1st Cavalry ground forces to annihilate the three NVA regiments at Chupong.

And for failing to be aware that the Ia Drang battle was a diversionary maneuver in support of the main action executed by a B-52 airstrike, Daddis's narration of this battle in his dissertation is way off the mark. Following is an excerpt from the dissertation about the Ia Drang battle (page 124-133); some inaccurate statements are highlighted.

Establishing the New Benchmark

On 1 July 1965, the 1st Cavalry Division officially came into existence. On 2 August, in a feat of logistical and administrative planning, the unit began its deployment to South Vietnam. Westmoreland placed the division near An Khe in western Binh Dinh province in the central highlands. COMUSMACV intended the 1st Cavalry to screen the Cambodian border while preventing North Vietnamese units from controlling the critical Highway 19 which linked Pleiku city in the highlands to Qui Nhon on the eastern coast. Hanoi had been closely monitoring the U.S. buildup and replied by increasing the infiltration of its forces and supplies into South Vietnam. The mountainous, rugged terrain of the central highlands offered advantages as NVA base areas thanks to its inaccessibility to ground transport, especially in the monsoon season from mid-May to mid-October. MACV considered the area vitally important as well. If North Vietnamese regulars wrested control of Highway 19 from ARVN they essentially would cut the country in half. Accordingly, 1st Cavalry troopers carved out a base camp at An Khe—nicknamed the “Golf Course”—and immediately began “shakedown” exercises in preparation for their expected baptism of fire with the enemy. The division did not have to wait long. In early October, as Kinnard’s men gradually expanded operations to find the enemy and establish governmental control in the VC-dominated region, Hanoi ordered General Chu Huy Man to undertake a series of engagements around Pleiku. Three North Vietnam Army (NVA) regiments joined the local Vietcong forces. On 19 October, they attacked the small U.S. Special Forces Plei Me camp near the Cambodian border. NVA forces quickly pounced on the South Vietnamese relief column that Man correctly had anticipated. (1) On the 23rd Kinnard received permission from Westmoreland to transfer his entire 1st Brigade to Pleiku, only twenty-five miles away. Relying heavily on artillery and tactical air support, the Americans responded with overwhelming firepower. By the 25th, Man decided he had suffered enough and withdrew westward to the northern bank of the River Drang near Cambodia. The MACV monthly eval for October cheerfully noted the engagement “permitted an extensive and effective utilization of Allied air power to strike the Viet Cong force.” However, not all participants were so optimistic. One of Kinnard’s helicopter pilots recalled, “With all our mobility, the VC still called the shots. We fought on their terms.” The young warrant officer’s observations were accurate. Man had determined when to attack and when to withdraw.55

Having tasted enemy blood—Americans estimated North Vietnamese losses at 850 dead and 1,700 wounded—Kinnard wanted desperately to continue the pursuit. The successful Plei Me defense hardly illustrated the full capacity of the airmobility concept. (2) Lobbying MACV to unleash the division onto the offensive, Kinnard received authorization on 28 October to pursue Man’s withdrawing units. UH-1 Huey helicopters swarmed the skies over Pleiku province as 1st Cavalry soldiers roamed the desolate brush in search of enemy forces. Between 28 October and 14 November, division troopers only sporadically came into contact with NVA forces which were being reinforced by nearly 2,000 soldiers from Man’s reserve regiment. As the number of American air assaults and artillery moves multiplied, MACV turned greater attention to filling the airmobile division’s increasingly critical fuel shortages. (3) Colonel Thomas W. Brown, whose 3rd Brigade relieved the 1st Brigade on 9 November, underlined the frustration—“having drawn a blank up to this point, I wasn’t sure what we would find or even if we’d find anything.” 56

Apparently helicopters had not cracked the puzzle of the intelligence battle. (4) Kinnard continued to press west toward the Cambodian border, directing Lieutenant Colonel Harold G. Moore’s 1 st Battalion, 7th Cavalry to search the Ia Drang valley near the Chu Pong Mountain area. Moore expected to make contact and on 4 November, after an early aerial reconnaissance of prospective landing zones (LZs), his battalion of 431 men began their flights deeper into the western plateau.

Moore’s suspicions of enemy presence were well founded. (5) Man in fact had consolidated his forces within the Chu Pong massif awaiting the Americans’ next move. Moore selected his LZ, X-Ray, right below the NVA position. The U.S. battalion commander, however, was no easy target. A 1945 West Point graduate, Moore had served as an infantry company commander in the Korean War and held a master’s degree in international affairs from George Washington University. The pragmatic forty-three year old Kentuckian had read Bernard Fall’s Street Without Joy and, though exacting in his demands, engendered fierce loyalty in his subordinates. Shortly after landing at X-Ray, one of Moore’s patrols captured an enemy prisoner who reported North Vietnamese battalions in the nearby massif. Extending its perimeter towards Chu Pong, B Company collided with two NVA companies triggering some of the most ferocious fighting of the entire war. Dennis Deal, a platoon leader in B Company working up a ravine, remembered “that at any given second there were a thousand bullets coursing through that small area looking for a target—a thousand bullets a second.” Correspondent Neil Sheehan recalled X-Ray “was not hard to distinguish from the air on Monday morning. It was an island in a sea of red-orange napalm and exploding bombs and shells.” 57

Despite the Americans’ heavy use of firepower, NVA infantrymen continued to surge out of Chu Pong towards Moore’s battalion. That the 7th Cavalry traced its lineage to Custer and Little Big Horn was not lost on the embattled troopers. By early afternoon, Moore was fighting three separate actions: defending the landing zone, attacking the North Vietnamese, and attempting to rescue a platoon which had earlier pursued an NVA patrol and been cut off from the rest of the battalion. Outnumbered, he pulled back to establish a perimeter and called in waves of artillery fire and tactical air strikes to keep the enemy at bay. Moore remembered the shells “falling down in torrents.” Helicopter pilots braved the storm of steel enveloping the LZ, transferring ammunition and reinforcements to and the growing number of wounded from the battlefield. (6) So desperate had Moore’s position become that MACV authorized the use of B-52 strategic bombers from Guam for close air support. On 16 November, unable to break the cavalry’s perimeter, the NVA commander, as at Plei Me, decided he could do no more against American firepower and began withdrawing his forces from the landing zone area.58

While the fighting at X-Ray died down, the North Vietnamese infantry were not quite done with the Americans. On 17 November, Lieutenant Colonel Robert A. McDade’s 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, en route to X-Ray as reinforcement, received orders to turn north and sweep the area for enemy soldiers before evacuating from a new LZ code-named Albany. McDade had been in command for only three weeks and took few precautions as he set out. The 8th Battalion of the 66th PAVN Regiment, heading in the same direction, found the American unit through careful scouting and immediately began establishing an ambush. Under deep jungle canopy, McDade’s men walked headlong into a trap. The melee, confusing as it was deadly, continued throughout the afternoon as pilots, often unable to distinguish between friend and foe, vainly attempted to provide support through the thick foliage. One soldier recalled, “Men all around me were screaming. The fire now was a continuous roar…. No one knew where the fire was coming from, and so the men were shooting everywhere. Some were in shock and were blazing away at everything they saw or imagined they saw.” Throughout the night, the NVA maintained their pressure on the encircled American perimeter. At daybreak they silently melted away. McDade’s unit had suffered 151 killed, 121 wounded, and five missing—over sixty percent casualties. Afterwards, Kinnard reported the “cavalry battalion had taken everything the enemy could throw at it, and had turned on him and had smashed and defeated him.” 59

Moore’s actions at LZ X-Ray quickly, perhaps predictably, eclipsed McDade’s at Albany. Yet was the Ia Drang battle really a victory? U.S. officials quickly hailed it as such based on familiar metrics. Discounting the catastrophe at Albany, MACV focused on the satisfyingly low ratio of American to enemy casualties. Body counts revealed Moore’s troopers killed 634 NVA soldiers—while “estimating” another 1, 215—compared to losing 75 killed and 121 wounded. (MACV did not publicize McDade’s losses.) To MACV, such casualty ratios demonstrated the validity of the airmobile division’s use of firepower and mobility. Body counts also appeared to validate MACV’s long-term objective of breaking the enemy’s will through a strategy of attrition.60 Through conventional lens, Westmoreland later celebrated the 1st Cavalry’s apparently decisive victory. “We had no Kasserine Pass as in World War II, no costly retreat by hastily committed, understrength occupation troops from Japan into a Pusan perimeter as in Korea.” 61 American troops, bearing technologically advanced weaponry, had stood their ground against the finest troops North Vietnam could offer. More, they inflicted a greater number of casualties and sent the enemy fleeing from the battlefield.

Just as predictably, the North Vietnamese embraced a different view of their first large-scale battle with the Americans. Common infantry soldiers had withstood the firestorm of American airpower and heliborne assault tactics. As Moore recalled, by Hanoi’s “yardstick, a draw against such a powerful opponent was the equivalent of a victory.” 62 More importantly, American firepower could be effectively countered, as seen during the destruction of McDade’s forces at Albany. By closing in tight with the 1st Cavalry troopers, the NVA could negate U.S. advantages in weaponry. (7) One former PLAF general officer remembered “the way to fight the American was to ‘grab him by his belt’…to get so close that your artillery and air power were useless.” 63 While Americans rejoiced in their victory at Ia Drang, they failed to consider that their new airmobile tactics might have an Achilles’ heel. (8) It seemed not to faze any of the 1st Cavalry Division or MACV’s leadership that B-52 bombers were needed to save Moore’s battalion. Hanoi’s leadership arguably took a more balanced appraisal of the fighting in Pleiku province. Helicopter assaults could be disrupted successfully but only at a heavy price. It was not yet time to progress into the final conventional phase of revolutionary war.

The 1st Cavalry’s spoiling attack into the western central highlands certainly derailed General Man’s plan to control Highway 19 and strike toward the coast before U.S . troops gained a significant foothold in South Vietnam. Ia Drang, however, hardly validated airmobility’s success in counterinsurgency operations. MACV misinterpreted, if not ignored, a number of significant facts in evaluating Kinnard’s Pleiku campaign. At Plei Me, X-Ray, and Albany the enemy initiated fighting and decided when to withdraw. Further, the North Vietnamese operated in battalion-sized formations, an option they would henceforth consider sparingly. Finally, destruction of enemy forces did not necessarily equate to population control. Tying military success in the central highlands to pacification progress along the coastal plains eluded MACV from the start.64

Justifiably inspired by the heroic performance of his young soldiers, Moore likely missed all the subtleties of evaluating progress in an unconventional war. In fact, most all of MACV’s officers chose to define success in November 1965 in narrow, conventional terms—in terms of combat effectiveness exhibited by American forces rather than of progress in the war against the southern insurgency. The “Significant Victories and Defeats” annex of MACV’s eval report that month consisted of five full pages of friendly and Vietcong losses. Nowhere did the annex mention pacification, civil affairs, or training of ARVN forces. Despite Westmoreland’s comprehensive strategy, staff officers at MACV made little effort to assess whether such hard statistics yielded any political “victories” against the enemy .65

Certainly a few Americans appreciated that helicopters had not wrested the initiative from either the Vietcong or the NVA. If official channels conveyed little doubt, some U.S. soldiers expressed their suspicions of airmobility’s touted invincibility to the media. After the Pleiku battles, New York Times military correspondent Hanson W. Baldwin recounted how some 1st Cavalry officers questioned both the airmobile division’s staying power and the number of ground forces needed to effectively search out and destroy the enemy. Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist and photographer Malcolm W. Browne quoted one U.S. advisor who doubted airmobility’s utility in a counterinsurgency environment. The officer noted “the Viet Cong have no helicopters or airplanes. They didn’t have any during the Indochina War either, but they still won.” The advisor then offered a veiled critique of the airmobility concept and the larger American approach to revolutionary warfare in Vietnam. “After all, when you come to think of it, the use of helicopters is a tacit admission that we don’t control the ground. And in the long run, it’s control of the ground that wins or loses wars.” 66 Such introspection hardly occurred within MACV’s own assessments of the recent Pleiku campaign, speaking volumes to the integrity of the evaluation system that was measuring effectiveness and progress in the field.

In reality, the 1st Cavalry Division’s “success” temporarily alleviated the confusion created by MACV’s abundant measurements of effectiveness. Ia Drang served to reduce the clutter of excessive metrics and provide army officers with an organizationally and culturally comfortable indictor for success: the exchange ratio. Traditional concepts of firepower and maneuver still mattered. Victory could still be defined by the destruction of any enemy unit. In the aftermath of Ia Drang, many army officers seemed not to consider, as Westmoreland had earlier mused, that if NVA regiments could be so decisively defeated in the field by American firepower they might realize the futility of fighting conventionally and revert to guerrilla tactics. The U.S. Army simply believed it could impose its will on a peasant army and society. In the process, MACV took the “estimation” of enemy dead in Moore’s after action report at face value.

It appears in late 1965 only Army Chief of Staff Harold K. Johnson questioned the 1st Cavalry Division’s battlefield results. Johnson cabled Westmoreland that he believed the NVA had repositioned in early January 1966 “to pounce on the Cavalry. In contrast, the picture painted by the Cavalry is that the PAVN were driven from the field…. I now have some rather serious doubts about this.” 67 Johnson’s reservations aside, Kinnard’s cavalrymen validated for MACV airmobility’s effectiveness in a counterinsurgency role. Doctrine stressed aggressiveness in maintaining continuous pressure on enemy forces. “Superior mobility is essential in counterguerrilla operations,” the army’s field manual noted, “to achieve surprise and to success fully counter the mobility of the enemy force. The extensive use of airmobile forces, if used with imagination, will ensure the military commander superior mobility.” 68 Ia Drang thus served to confirm U.S. counterinsurgency doctrine as sound. The army’s leadership never considered that the conventional three-brigade organization of divisions like the 1st Cavalry might, in fact, be ill suited for small-scale counterinsurgent operations. Officers flushed with success discounted problems with their innovative organization. Under battlefield conditions, the airmobile division proved to MACV that traditional concepts of mobility and firepower could successfully defeat the enemy in South Vietnam.69

(9) By using new airmobile techniques, the 1st Cavalry seemed to achieve victory in the Ia Drang using standard, conventional operations. Moore had attacked and defended, terms that any World War II or Korean War veteran could comprehend. Thus, the metrics determining effectiveness of such operations did not require alteration. For the military component of Westmoreland’s strategy, Moore’s troopers had established the benchmark. If terrain could not serve as a scorecard, the body count would help keep tally. Kinnard’s official after action report noted that “when results of any action or campaign are assessed, statistics must be utilized. In many cases it is the only way results can be shown in a tangible manner and, therefore, readily grasped.” 70 The report then proceeded to discuss its breakdown of enemy casualties, weapons captured, and friendly losses. Statistical analysis came through the Ia Drang battle as unscathed as MACV’s faith in helicopters. Among those statistics, however, the body count rose to the dominant indicator for success in the minds of many officers. Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore had set the standard for the army, killing an “estimated” 1,849 enemy soldiers in only a few days of fighting. Surely other officers would want to follow in his footsteps.

52 Kinnard quoted in Johnson, Winged Sabers, 5. On American reliance on technology, see Kolko, Anatomy of a War, 188 and Baritz, Backfire, 51. On the capabilities of helicopters, see Department of the Army, Field Manual 57-35, Airmobile Operations, September 1963, 4.

53 French experience in Bernard F. Fall, Street Without Joy (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1961, 1994), 361. On ideology and technology, see Marilyn B. Young, The Vietnam Wars, 1945-1990 (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), 112. The deputy director of the State Department’s Vietnam Working Group wrote in August 1962: “Politics is people. People don’t change quickly. Helicopters can move fast; attitudes take longer.” FRUS, 1961-1963, II: 571.

54 1st Cavalry deployment in Carland, Stemming the Tide, 54-62. On central highlands encampment, see: Wilbur H. Morrison, The Elephant and the Tiger: The Full Story of the Vietnam War (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1990), 188; Robert B. Asprey, War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1975), 1112; and Moyar, Triumph Forsaken, 392. Shakedown exercises in Stanton, Anatomy of a Division, 46-47. North Vietnamese infiltration in JCS History, Part II, JCSHO, 22-1. The divisional spokesman noted in early October that “we are not tied to the jungle or the paddies. We can avoid ambush. We fly over it and strike unexpectedly.” In “1 st Cavalry Brings Mobility to War Against Viet Cong,” Minnesota Tribune, 10 October 1965.

55 MACV Monthly Evaluation Report, October 1965, MHI, 2. Robert Mason, Chickenhawk (New York: The Viking Press, 1983), 101-102. Plei Me battle in Carland, Stemming the Tide, 99-104. Herring, America’s First Battles, 309-313. The NVA regiments taking part in the campaign were the 32nd, 33rd, and the 66th which was held in reserve.

56 Losses in the Plei Me battle from Herring, America’s First Battles, 313. Brown quoted in Stanton, Anatomy of a Division, 55. On the lead up to Ia Drang, see Carland, Stemming the Tide, 104-111 and Stanton, Rise and Fall, 56-57. The 1st Brigade made significant contact on 6 November, running into a well-placed ambush that pinned down a battalion’s worth of American soldiers. Herring, America’s First Battles, 315.

57 Moore biographical sketch in Coleman, Pleiku,187. Deal in Christian G. Appy, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides (New York: Viking, 2003), 131. Neil Sheehan, A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam (New York: Random House, 1988), 573. The best account of the battle, and a fine piece of military history, is Harold G. Moore and Joseph L. Galloway, We Were Soldiers Once...and Young (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 1993). On artillery fires initially being ineffective, see John A. Cash, John Albright, and Allan W. Sandstrum, Seven Firefights in Vietnam (Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publishers, Inc., 2007), 17.

58 Moore, We Were Soldiers Once, 133. On fighting three separate actions, see Coleman, Pleiku, 205. Use of B-52 bombers from Herring, America’s First Battles, 319.

59 Quotation from Jack P. Smith, “Death in the Ia Drang Valley,” Saturday Evening Post Vol. 240, No. 2 (28 January 1967): 82. Harry W.O. Kinnard, “A Victory in the Ia Drang: The Triumph of a Concept,” Army Vol. 17, No. 9 (September 1967): 89. Albany ambush in Carland, Stemming the Tide, 136-145. Casualties on p. 145. Carland notes that the battalion’s daily journal from 16-22 November mysteriously vanished, helping the fight at Albany “disappear from official discussions of the Pleiku battles.” See also Stanton, Rise and Fall, 59-60.

60 Casualty numbers taken from After Action Report, Ia Drang Valley Operation, 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, 14-16 November 1965, 13. Copy of original report downloaded from www.lzxray.com. On low ratios confirming MACV’s attrition strategy, see Leslie H. Gelb with Richard K. Betts, The Irony of Vietnam: The System Worked (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institute, 1979), 135. Micheal Clodfelter called the battle of Ia Drang a “distinct victory for American firepower and mobility.” Vietnam in Military Statistics: A History of the Indochina Wars, 1772-1991 (Jefferson, N.C., London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1995), 71.

61 Westmoreland, A Soldier Reports, 191. See also Report on the War in Vietnam, 99. “The ability of Americans to meet and defeat the best troops the enemy could put on the field of battle was once more demonstrated beyond any possible doubt, as was the validity of the Army’s airmobile concept.” Harry G. Summers, Jr. argued that “it might have been better in the long run if we had lost this first battle, as we had lost the first major battle of World War II…. Our initial defeat in North Africa scared us with the knowledge that if we did not devise better strategies and tactics, we could lose the war.” See “The Bitter Triumph of Ia Drang,” American Heritage (February-March 1984): 58. By ignoring the political context of the war, Mark W. Woodruff offers a one-dimensional, naïve evaluation of how battles like Ia Drang were clear-cut victories for American forces. Unheralded Victory: The Defeat of the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, 1961-1973 (Arlington, Va.: Vandamere Press, 1999), 69-87.

62 Moore, We Were Soldiers Once, 399. For Hanoi’s assessment of the fighting, see Victory in Vietnam, 159-160.

63 Hoang Anh Tuan quoted in Cecil B. Currey, Victory at Any Cost: The Genius of Viet Nam’s Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap (Washington, London: Brassey’s, Inc., 1997), 257. General Vo Nguyen Giap recalled, “You planned to use [air mobile] tactics as your strategy to win the war. If we could defeat your tactics—y our helicopters—then we could defeat your strategy.” Ib id. On early enemy reactions to U.S. helicopters in 1962, see Tolson, Airmobility, 26-27. On the enemy’s capability at countering U.S. advantages in firepower, see Carland, Stemming the Tide, 149 and Rosen, Winning the Next War, 94.

64 Palmer noted “Victory in Vietnam was hard to measure.” Palmer went on to argue, however, that “the outcome of the fighting along the Ia Drang and under the Chu Pong was a victory in every sense of the word.” Summons of the Trumpet, 102. On success of 1st Cavalry’s spoiling attack, see Kinnard, “A Victory in the Ia Drang,” 72. On MACV overlooking important facts, see Krepinevich in Showalter, An American Dilemma, 96. On Army Chief of Staff Harold K. Johnson’s views of destruction versus control, see Sorley, Honorable Warrior, 201.

65 MACV Monthly Evaluation Report, November 1965, Annex E, 31-35, MHI. Although Moore acknowledged this issue in We Were Soldiers Once...and Young, 398-401.

66 Advisor quoted in Malcolm W. Browne, The New Face of War, rev. ed. (Indianapolis, New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1968), 79. Hanson Baldwin, “U.S. First Cavalry is Sternly Tested,” The New York Times, 20 November 1965. On asking how much increase in mobility helicopters actually provided, see James H. Pickerell, Vietnam in the Mud (Indianapolis, New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1966), 45. See also Gerard J. DeGroot, A Noble Cause? America and the Vietnam War (Harlow, Essex: Longman, 2000), 149.

67 Johnson in The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War, Part IV, 101-102. On self-delusion in the army, see Herring, LBJ and Vietnam, 37. Zaffiri notes the massive amounts of firepower rushed in to save the beleaguered 1st Cavalry, an aspect of the fighting not highlighted by MACV. Westmoreland, 152.

68 Field Manual 31-16, 21.

69 On narrow lessons from the campaign, see Benjamin S. Silver and Francis Aylette Silver, Ride at a Gallop (Waco, Tx.: Davis Brothers Publishing Co., 1990), 316. See also Coleman, Pleiku, 267-269. On conventional organizations potentially not being suited to counterinsurgency, see Boyd T. Bashore, “Organization for Frontless Wars,” Military Review Vol. XLIV, No. 5 (May 1964): 16. On discounting dangerous weaknesses, see Palmer, Summons of the Trumpet, 97. DeGroot maintains that “helicopters provided the illusion of offensive mastery.” A Noble Cause?, 149.

70 Operations Report, Lessons Learned, 3-66, The Pleiku Campaign, 10 May 1966, CMH Library, 213. On MACV requiring no more feedback other than body counts, see Krepinevich, The Army and Vietnam, 169.

(1) On the 23rd Kinnard received permission from Westmoreland to transfer his entire 1st Brigade to Pleiku, only twenty-five miles away. Relying heavily on artillery and tactical air support, the Americans responded with overwhelming firepower.

= However, although he did transfer the entire 1st Brigade to Pleiku, only one infantry battalion – 2/12 Air Cav - was assigned to defend the Pleiku airfield/Pleiku City and one artillery battalion -Battery B, 2/17 Arty - was helilifted to Phu My to lend support to the ARVN Armored Relief Task Force. The rescue mission of Pleime, remained under the responsibility of ARVN II Corps Command.

(2) Lobbying MACV to unleash the division onto the offensive, Kinnard received authorization on 28 October to pursue Man’s withdrawing units.

= However, Kinnard did not get “carte blanche” per se; the 1st Air Cav Division remained under the tight control of General Larsen of IFFV who intervened several times and issued tactical orders during 1st Air Cav Division’s operations. According to Coleman ("Pleiku, the Dawn of Helicopter Warfare in Vietnam", St. Martin’s Press, New York.):

On 11/7

Despite this plethora of intelligence to the contrary at the field command level, Kinnard, acting on the orders from Task Force Alpha (the American command’s euphemism for a corps headquarters), told Brown to begin his search south and east of Plei Me. For some reason, Swede Larsen and his staff, and probably the operations and intelligence people up the line at MACV as well, were convinced that some of the North Vietnamese had slipped away to the south and east to the hill country about fifteen kilometers from the Plei Me camp, and they were adamant that the Cav should start turning over rocks in that area.

On 11/13 (Coleman):

The last of the 1st Brigade’s units departed the area of operations, bound for An Khe, and the third of the 3rd Brigade’s three maneuver battalions arrived. All three battalions now were working the color-coded search areas generally between Plei Me camp and Highway 4. It had been a dry hole for everyone, and General Knowles and Tim Brown were getting impatient and starting to look longingly toward the west. Knowles had long wanted to stage some kind of operation inside the Chu Pong Massif.

[…]

That day, General Larsen was visiting the division’s forward command post at the II Corps compound. He asked Knowles how things were going. Knowles briefed him on the attack on Catecka the night before and then told him the brigade was drilling a dry hole out east of Plei Me. Larsen said, “Why are you conducting operations there if it’s dry?” Knowles’s response was, “With all due respect, sir, that’s what your order in writing directed us to do.” Larsen responded that the cavalry’s primary mission was to “find the enemy and go after him.” Shortly after, Knowles visited Brown at the 3rd Brigade command post and told him to come up with a plan for an air assault operation near the foot of the Chu Pongs.

On 11/14 (Coleman):

General Knowles had been at the division’s TOC when the first news of the contact came in. He piled into his command chopper and headed for Catecka, where Brown briefed him. Both commanders realized that they had stirred up a hornet’s nest that would take more troops to quell than Brown had available. Knowles got on the horn and called Harry Kinnard back at An Khe, asking for another infantry battalion, more artillery, and both troop- and medium-lift helicopters. Kinnard replied, “They’re on the way, but what’s going on?” Knowles responded, “We’ve got a good fight going. Suggest you come up as soon as possible.” After setting the reinforcement wheels in motion, Kinnard choppered over from An Khe and met Knowles at Catecka. When he arrived, Knowles showed him the situation map he had propped up against a palm tree. Kinnard took one look and said, “What the hell are you doing in that area?” Obviously, someone hadn’t kept the boss informed about Larsen’s guidance to get after the enemy even if it meant walking away from the dry holes in the east. Knowles told Kinnard, “The object of the exercise is to find the enemy, and we sure as hell have!” Knowles remembers an awkward pause before Kinnard said quietly, “Okay, it looks great. Let me know what you need.”

(3) Colonel Thomas W. Brown, whose 3rd Brigade relieved the 1st Brigade on 9 November, underlined the frustration—“having drawn a blank up to this point, I wasn’t sure what we would find or even if we’d find anything.”

= Colonel Brown, at the brigade level, seemed not to be in the purview of the scheme designed by higher up echelons in making the enemy believe that the operational forces had lost track of the enemy troops. As a matter of fact, during the period of October 27 to November 11, B2/1st Air Cav and B2/II Corps had been monitoring closely the whereabouts of the various units of the three NVA regiments (Intelligence Aspects of Pleime-Chupong campaign):

On 10/27, the lead elements of the 33d had closed on it forward assembly area, the village Kro (ZA080030); on 10/28, the 32d Regiment had nearly closed its base on the north bank of the Ia Drang; on 10/29, the 33d Regiment decided to keep the unit on the move to the west, to Anta Village (YA940010), located at the foot of the Chu Pong Massif; on 11/1, the 33rd regiment headquarters closed in at Anta Village; on 11/2, by 0400 hours, the 2d, the regimental CP had arrived at Hill 762 (YA885106); on 11/05, units of 66th Regiment continued to close in the assembling areas in the Chupong-Iadrang complex; on 11/07, the depleted 33d Regiment licked its wounds and waited for its stragglers to come in, meanwhile the remainder of Field Front forces were quiet; on 11/08, only fragmented units and stragglers remained east of the Chu Pong-Ia Drang complex; on 11/09, the 33d Regiment gathered in the last of its organic units; on 11/11, the three battalions of the 66th Regiment were strung along the north bank of the Ia Drang river (center mass at 9104), the 32nd Regiment was also up north in the same area (YA820070), the 33rd Regiment maintained its positions in the vicinity of the Anta Village, east of the Chu Pong mountains.

(4) Kinnard continued to press west toward the Cambodian border, directing Lieutenant Colonel Harold G. Moore’s 1 st Battalion, 7th Cavalry to search the Ia Drang Valley near the Chu Pong Mountain area.

= Kinnard did not press toward the Cambodian border and did not direct LTC Moore’s 1/7 Air Cav into the Chu Pong Mountain area. He stated with Cochran ("First Strike at River Drang", Military History, Oct 1984, pp 44-52, Per. Interview with H.W.O Kinnard, 1st Cavalry Division Commanding General.):

The choice to go into the Chu Pong, a longtime enemy sanctuary [near the Cambodian border] into which ARVN had never gone, was not mine. It was either that of General Knowles or the brigade commander. We hadn't looked at the area. It wasn't intelligence that led us there. If anything, it was the lack of intelligence, and this seemed a logical place.

(5) Man in fact had consolidated his forces within the Chu Pong massif awaiting the Americans’ next move.

= Man did not consolidate his forces and waited for the American’s next move. He regrouped his three regiments in Chu Pong massif in order to stage for a second attack of Pleime camp (Pleime, Trận Chiến Lịch Sử, page 94):

Dan Thang 21 operation finished, Pleime camp was back on its footing, but among the two VC Regiments that had joined in the attack, we only inflicted the enemy with more than 400 killed. The withdrawal was a rational and intelligent initiative taken by the VC Field Front Command. But the enemy would attempt to take revenge, and furthermore, the remote Pleime camp remains an eyesore to them.

(6) So desperate had Moore’s position become that MACV authorized the use of B-52 strategic bombers from Guam for close air support. On 16 November, unable to break the cavalry’s perimeter, the NVA commander, as at Plei Me, decided he could do no more against American firepower and began withdrawing his forces from the landing zone area.

= Moore’s position had never reached the point of desperation. 1/7 Air Cav was always reinforced with sufficient troops to hold its defensive perimeter: B/2/7 Air Cav at 6:00 pm on November 14; at 9:15 am on the next day November 15, the entire 2/7 Air Cav was present at LZ X-Ray; and at 12:05 pm on the same day, 2/5 Air Cav closed in to rescue the isolated platoon.

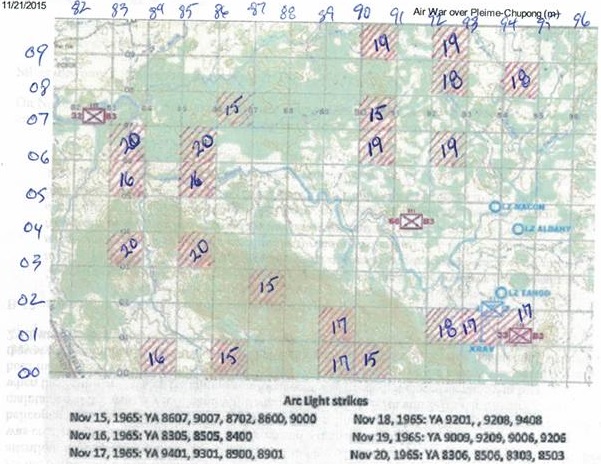

B-52 bombers did not lend close air support to 1/7 Air Cav. It was the reverse: 1/7, 2/7 and 2/5 Air Cav fixed the three NVA regiments into targets to allow B-52 bombers sufficient time to come from Guam on an eight-hour flight. The first waves of bombs were dropped at 4:00 pm on November 15 over the positions of 32nd and 33rd NVA Regiments (G3 Journal/IFFV):

- 11/15/65 at 10:30H: MAVC J3 (Gen DePuy) Gen DePuy called Col Barrow and asked if Arc Light had been cleared with CG II Corps. Col Barrow replied yes, CG II Corps had approved Arc Light. Target area approved by Col Barrow and Col McCord. Also Gen DePuy wanted to know if the elem of 1st Cav had received the 151600H restriction on not going west of YA grid line. Col Barrow informed Gen De Puy that the 1st Cav had acknowledged receipt of the restriction and would comply. Gen DePuy personally changed target configuration.

Only on November 17 that B-52 bombers struck the LZ X-Ray itself (Pleiku campaign, page 94):

Those troops still remaining in the now deserted X-Ray area suddenly learned of the reason for the exodus of the cavalry. A B-52 strike had been called in virtually on top of the old positions.

(7) One former PLAF general officer remembered, “the way to fight the American was to ‘grab him by his belt’…to get so close that your artillery and air power were useless.”

= That PLAF general officer did not realize though that his troops were not facing combat with ground units that could be ‘grab by the belt’ but were rather annihilated by B-52 airstrikes that came down over their heads with the American ground troops standing at a 3-kilometers distance.

(8) It seemed not to faze any of the 1st Cavalry Division or MACV’s leadership that B-52 bombers were needed to save Moore’s battalion.

= This observation is dead wrong considering that the use of B-52 bombers was pre-planned as the main force to destroy the three NVA regiments in Chupong with 1st Air Cav troops playing a secondary role and performing a diversionary maneuver in support of the B-52 airstrike (Intelligence Aspects of Pleime-Chupong campaign, page 6):

The Chu Pong base was known to exist well prior to the Pleime attack, and J2 MACV had taken this area under study in September 1965 as a possible B-52 target.

(9) By using new airmobile techniques, the 1st Cavalry seemed to achieve victory in the Ia Drang using standard, conventional operations.

= When 1st Cavalry troops entered Ia Drang, they did not use the new airmobile techniques of air assaults which consisted in searching the enemy with a company size of troops, and when the enemy is found, fixing them with an engagement, then rapidly piling in more troops needed to destroy the entrapped enemy units (Cochran):

Right after the Plei Me siege was broken, I felt that it was up to me to find these guys who had been around the camp. So we came up with a search “modus operandi” in which the Cav Squadron was going to range widely over a very large area and I was going to use one infantry brigade to plop down an infantry battalion and look at an area here and there. I felt that we had to break down into relatively small groups so we could cover more area and also the enemy would think he could fake us. You couldn’t put down a whole battalion out there and go clomping around. You had to break down into company and platoon-sized units. You had to rely upon the fact that with the helicopter you could respond faster than anyone in history. I then learned, totally new to me, that every unit that was not in contact was, in fact, a reserve that could be picked up and used. This is my strategy. Start from somewhere, break down into small groups, depending upon the terrain, and work that area while the Cav Squadron roamed all over. The name of the game was contact. You were looking for any form of contact – a helicopter being shot at, finding a campfire, finding a pack, beaten-down grass.

Instead, 1st Air Cav’s mission in landing at LZ X-Ray was a diversionary tactic aiming only at fixing the three NVA regiments at their assembly positions to allow B-52 bombers to strike by holding its defensive perimeters in a blocking position and not spreading out in pursuit of the enemy troops. This explains why 1/7 Air Cav was extracted on November 16 and 2/7 and 2/5 Air Cav on November 17.

General Knowles reveals that the purpose of the insertion of the Air Cavalry troops at LZ X-Ray on November 14 was to “grab the tiger by its tail” and to hit its head with B-52 airstrikes from November 15 to 16. He also explains the reason for pulling out of LZ X-Ray on November 17 and moving to LZ Albany was “to grab the tiger by its tail from another direction” and continued to hit its head with B-52 bombs from November 17 to 20.

Conclusion

Since it is a scholarly essay, Daddis took great care in relying on his account of the Ia Drang battle on reliable references comprising primary sources and personal accounts of participants of the battle. However his study was not comprehensive and in-depth enough, which leads him to misinterpret and to misunderstand what really happened at Ia Drang battle: that it was just a piece of action in the vast scheme - that needed 38 days and 38 nights to carry out - of using B-52 airstrike to annihilate the three NVA regiments at Chupong massif. Daddis' shortcoming is typical and common in the current literature pertaining to the Ia Drang battle.

Nguyen Van Tin

10 July 2014

- Operation Pleime-Chupong B-52 Strike?

- The Use of B-52 Strike in Ia Drang Campaign, General Westmoreland’s Best Kept Military Secret

- Air War Over Pleime-Chupong

- Arc Light over Chu Pong Operation

- Catching a Thief Tactic in Pleime Campaign

- Pleime/Chupong Campaign Destroying B3 Field Front Base

- The Uniqueness in Pleime Counteroffensive Operational Concept

- Pleime Counteroffensive into Chupong Iadrang Complex

- The Unfolding of Strategic and Tactical Moves of Pleime Campaign

- Battle of Pleime

- The Truth about the Pleime Battle

- Intelligence Gathering at Ia Drang

- Intelligence, the Key Factor in the Pleime Campaign's Victory

- Roll Call of Combatants at Pleime-Chupong-Iadrang Battlefront

- "Victory at Pleime" ?

- Tactical Moves in Pleime Battle

- Kung Fu Tactics at Pleime Campaign

- Various Diversionary Moves in Support of Arc Lite Strike in Pleime Counteroffensive

- What if there was no master plan for Pleime Counteroffensive?

- Pleime/Chupong Campaign Destroying B3 Field Front Base

- A Few Things You Should Know about Pleime-Iadrang Campaign

- Things the VC Don't Want People To Know at Pleime Battle

- Reviewing "Why Pleime"

- Review of "Intelligence Aspects at Pleime_Chupong Campaign"

- Perplexing Maneuvers at Pleime-Chupong-Iadrang You Might Be Attempted to Question

- A Bird’s-Eye-View of Pleime Campaign

- Operation Dan Thang 21

- US Air Force’s Roles in Pleime Campaign

- Arc Lite Operation Planning and Execution in Pleime Offensive

- A Doctrinal Lesson on the Use of Arc Lite in Pleime Counteroffensive

- Command and Control of Arc Light Strike at Chupong-Iadrang

- A Military Genius in Action at Pleime-Chupong-Iadrang Battlefront

- Command and Control Skills in Pleime Campaign

- Behind-the-scenes Activities at Various Allied Headquarters During Pleime Campaign

- The Two Principals Players Of Pleime Chess Game

- Pleime Battle's Diary

- Pleime Campaign and Pleiku Campaign

- A New Look at Ia Drang

- Operation Long Reach

- LZ X-Ray Battle (General Knowles)

- My Contributions to the Battle of Ia Drang in Wikipedia

- Operation LZ X-Ray

- Colonel Hal Moore’s Self-Aggrandizement in “We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young”

- Colonel Hal Moore Misunderstood his Mission at the Ia Drang Battle

- What Historians Failed to Tell About the Battle at LZ X-Ray

- Hal Moore and 1/7th Air Cavalry Battalion's Real Mission at LZ X-Ray

- Two Different Narrations of LZ X-Ray Battle by II Corps

- Ia Drang Valley Battle? Which One?

- LTC Hal Moore Summoned to a Woodshed Session?

- Colonel Hieu's Operational Concept for LZ X-Ray

- LZ Albany Battle - Chinese Advisors' Perspective

- A Puzzling Air Assault Performed by 1/7 Air Cavalry at LZ X-Ray

- Two Different Narrations of Than Phong 7 Operation by II Corps

- General Schwarzkopf's Naïveté In Ia Drang Battle

- Venturing into Lion's Den in Ia Drang Valley

- American Perspective of Pleime Battle

- General Kinnard's Naïveté in Pleime Campaign

- "No Time for Reflection at Ia Drang" ?

- Pleime Campaign or Pleime-Ia Drang Campaign?

- A Critique of General Bui Nam Ha's Opinions about Plâyme Campaign

- Commenting on General Nguyen Huu An's Account of Plâyme Campaign

- Crushing the American Troops in Western Highlands or in Danang?

- What Really Happened at Ia Drang Battle

- Case Study of a Typical Misinterpretation of Ia Drang Battle

- Ia Drang Battle Revisited

Documents

- Why Pleime

- Pleime, Trận Chiến Lịch Sử

- Pleime Battle Viewed From G3/I Field Force Vietnam

- Long Reach Operation Viewed From G3/I Field Force Vietnam

- LZ X-Ray Battle and LZ Albany Battle Viewed From G3/I Field Force Vietnam

- Than Phong 7 Operation Viewed From G3/I Field Force Vietnam

- Arc Light Strike at Chupong-Iadrang Viewed From G3/IFFV

- Pleiku Campaign

- Intelligence Aspects at Pleime_Chupong Campaign

- Excerpts of General Westmorland’s History Notes re: Pleime-Chupong-Iadrang Campaign

- LZ X-Ray Battle (General Knowles)

- LZ X-Ray After Action Report - LTC Hal Moore and Colonel Hieu

- Than Phong 7

- 52nd Combat Aviation Battalion in Support of Pleime Campaign

- CIDG in Camp Defense (Plei Me)

- Viet Cong Requested Red China's Aid

- Battle of Duc Co

- NVA Colonel Ha Vi Tung at Pleime-LZ Xray-LZ Albany

- The Fog of War: The Vietnamese View of the Ia Drang Battle

- No Time for Reflection: Moore at Ia Drang

- 1st US Cavalry Division Gives Support in the Battle at Plei Me

- Plei Me Fight Stands As War Turning Point

- Plei Me Battle

- Seven Days of Zap

- Pleime Through New York Times' View

- First Engagement With American Troops at Pleime-Iadrang

- Pleime Campaign

- Crushing the American Troops in Central Highlands

- NVA 66th Regiment in Pleime-Ia Drang Campaign

- The Political Commissar at the First Battle Against the Americans in Central Highlands