“We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young”

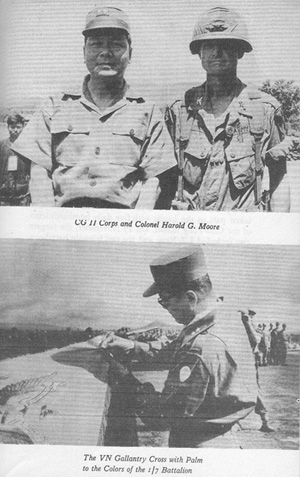

After the Ia Drang Valley battle, ARVN II Corps Command acknowledged 1/7th Air Cavalry Battalion’s heroism with VN Gallantry Cross with Palm. LTC Hal Moore’s battalion was attached to II Corps Forces in the 1965 Pleime Campaign.

In 1992, Lieutenant General Hal Moore and Joe Galloway decided to write the book We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young to “tell the American people what great Soldiers these are. Tell them what a great job they did and what a great Army we have” (Brian Sobel, 10 Questions for General Hal Moore). In his narrative of the epic battle, Moore was taken by self-aggrandizement in two aspects: his assigned mission in the battle and the degree of danger during the battle.

Assigned Mission

The mission assigned to Moore was to fix the three NVA Regiments – 32nd, 33r, and 66th – at their assembly areas about to move out to attack the Pleime camp for the second time, by conducting an airborne insertion at the footstep of Chu Pong Massif, next to the position of the 66th Regiment, which was the main force in this second attack. Once the distracting diversionary maneuver was achieved, the 1/7 Air Cavalry Battalion would be withdrawn.

LTC Moore did not read his superiors’ mind and thought he was sent in to search and destroy the enemy troops. That was why in the morning of November 15 he refused to relinquish the field command at LZ X-Ray to Colonel Tim Brown who landed down at the landing zone to set up a forward brigade command post to run the show and performed the withdrawal of 1/7 Air Cavalry Battalion with a troop rotation, replacing it with 2/7 and 2/5 Air Cavalry Battalions. His resistance to withdraw his battalion led to the subsequent intervention of General Knowles at the forward division headquarters level and of General Westmoreland/DePuy at the MACV headquarters level.

In his own words, Moore recounted in his book We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young :

- re: Brown (page 202)

Mid-morning, before Tully arrived, Colonel Tim Brown flew in for a visit. Plumley recalls: “Lieutenant Colonel Moore saluted Brown and said, ‘I told you not to come in here. It’s not safe! Brown picked up his right collar lapel and waggled his full colonel’s eagle at Moore and said, ‘Sorry about that!” Dillon and I gave him a situation report. Brown asked whether he should stay in X-Ray to establish a small brigade command post, and run the show. We recommended against that. I knew the area, and Bob Tully and I got along just fine. Brown agreed. Just before he departed, Colonel Brown told us that we had done a great job but now that Tully's fresh battalion was coming in, along with two rifle companies of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cav, he would likely pull us out of X-Ray the following day.

- re: Knowles (page 210)

Within half an hour after the Tully task force had returned to X-Ray Brigadier General Richard Knowles came up on the radio asking permission to land.

(…)

Before leaving, General Knowles told us that he would direct Tim Brown to pull my battalion and the attached units out of X-Ray the next day and fly us back to Camp Holloway for two days of rest and rehabilitation.

- re: Westmoreland/DePuy (page 216)

Around midnight [November 15] Lieutenant Colonel Edward C. (Shy) Meyer, 3rd Brigade executive officer, passed me an astonishing message: General William Westmoreland's headquarters wanted me to "leave X-Ray early the next morning for Saigon to brief him and his staff on the battle." I could not believe I was being ordered out before the battle was over! I was also perplexed that division or brigade HQ had not squelched such an incomprehensible order before it reached me. My place was clearly with my men.

(…)

Around 1:30 a.m., I got Shy Meyer on the radio and registered my objections to the order in no uncertain terms. I made it very clear that this battle was not over and that my place was with my men - that I was the first man of my battalion to set foot in this terrible killing ground and I damned well intended to be the last man to leave. That ended that. I heard no more on the matter.

It was obvious Moore misunderstood that his role was only secondary to the main role played by the B-52 airstrikes in the annihilation of the three NVA regiments at Chu Pong in refusing to withdraw his battalion in thinking this battle was not over and not recognizing that his assigned role of distracting the enemy’s attention was achieved and the presence of his battalion was no more needed.

The diversionary maneuver was planned as following: once its insertion caught the attention of B3 Field Front Command and distracted it from moving out to attack Pleime camp, 1/7 Air Cavalry Battalion was to withdraw. It would be reinforced with an appropriate number of units to match the enemy’s reactive forces. The actual operation unfolded as follows:

- By noon of November 14, General Knowles learned that B3 Field Front decided to counter-attack with only two battalions – the 7th and 9th of 66th Regiment. He added one more battalion to the air assault force (Coleman "Pleiku, the Dawn of Helicopter Warfare in Vietnam", St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1988, page 219):

Knowles got on the horn and called Harry Kinnard back at An Khe, asking for another infantry battalion, more artillery, and both troop- and medium-lift helicopters.

- By late afternoon of November 14, General Knowles decided to commit another battalion – the 2/5 Air Cavalry, in preparation of the withdrawal of 1/7 Air Cavalry Battalion scheduled for November 16 (1/7 AC after action report):

A. Late in the afternoon of 14 November, the brigade Commander had moved the 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, into LZ Victor. At approximately 0800 hours [November 15] it headed, on foot, for LZ X-RAY.

Managing the Military Situation at LZ X-Ray

Moore acknowledged that General Knowles and Colonel Brown were very thorough in exercising the control of the LZ X-Ray air assault operation (Moore, page 38):

Knowles, Brown, and I were comfortable with each other. We had worked together closely for the last eighteen months. They knew their stuff on airmobility and helicopter warfare, and I had gone to school on them. They knew they could count on me, and I knew they would provide all the support I needed, sometimes even before I knew I needed it.

General Knowles and Colonel Brown had taken all the necessary precautions in making sure the 1/7 Air Cavalry Battalion would face the minimum risk in conducting the diversionary maneuver in three key areas:

- 1/ The NVA troops did not have anti-aircraft guns to shoot down transport helicopters and heavy mortars to mauled down the infantry troops prior to ground assaults (Why Pleime, chapter V):

The enemy has lost nearly all their heavy crew-served weapons during the first phase. They had been surprised by the attack of the 1/7 battalion and their commanders had failed to make the best use of the terrain.

Helicopters ferrying troops, ammunition, supplies and medevacs that got hit at LZ X-Ray were shot at only by small fire arms.

General Kinnard also pointed out that (Pleiku campaign, page 88):

The NVA effort unquestionably was hampered by the unexplained delay in getting the heavy mortar and heavy anti-aircraft battalions off the infiltration trail and into the battle zone.

- 2/ At all time during the battle, the American units on the ground (1/7, 2/7 and 2/5) were always at least at par if not superior to the NVA two reactionary Battalions – the 7th and 9th of 66th Regiment (General Nguyen Huu An’s Memoire):

At the forward command post, we grasped a better control of the situation at this moment. 66th Regiment reported back: 9th Battalion was able to establish communication with 7th Battalion. Thus, the balance of forces in this narrow area was two battalions for each side, with the American side higher in troop numbers, not counting two artillery companies and air force enforcements.

- 3/Through real-time intelligence obtained with radio intercepts of enemy’s communications provided by G2/II Corps, General Knowles and Colonel Brown knew exactly all intentions, planning and moves generated from B3 Field Front Forward: its decision to postpone the attack of Pleime camp and to commit only two battalions to counter the American attack troops. The monitoring of the real-time intelligence also allowed General Knowles and Colonel Brown to assess the level of pressure the enemy troops exerted against the Air Cavalry troops at LZ X-Ray which allowed them to land with safety assurance at LZ X-Ray at 4:30 pm and 9:30 am on November 15, respectively.

- 4/Furthermore, Hal Moore’s 1/7 Air Cavalry Battalion, once inserted at LZ X-Ray, was heavily protected by “a ring of steel” put up by the Division Artillery. Knowles had “every route into and out of the area hit hard around the clock” - to interdict NVA troops of the 32nd and 33rd to come in the area. (Richard T. Knowles Collection, The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University, p. 4)

In his 1/7 AC after action report, Moore was surprised that, around 7:30 am on November 15, his need for reinforcement was anticipated by Colonel Tim Brown, his brigade commander the night before:

I radioed the brigade commander, informed him of the situation, and in view of the losses being sustained by C Company and the heavy attack, I requested an additional reinforcing company. He had already alerted Company A, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry the previous night and assembled it with helicopters ready for movement.

He also learned that Colonel Tim Brown had 2/5 Air Cavalry Battalion ready as early as Nov 14 to reinforce the 1/7 and 2/7 the next morning:

A. Late in the afternoon of 14 November, the brigade Commander had moved the 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, into LZ Victor. At approximately 0800 hours [November 15] it headed, on foot, for LZ X-RAY.

Moore did not know that his 1/7 Air Cavalry Battalion was to be replaced by the two 2/7 and 2/5 Air Cavalry Battalions.

Dramatizing the Facts

Moore gave himself credit for the selection of the insertion landing zone. He wrote on page 64 of his book :

Colonel Tim Brown had told us generally where he wanted us to operate after the landing, but we now had to select a landing zone, and preferably one that would take as many of our sixteen Hueys as possible at one time.

General Knowles begs to differ. Jack Swickard writes in, "Friendship with military legend" (Swickardworld, Friday, October 11, 2013):

Once, when I visited with Dick about the battle, he told me he had selected the initial landing zone used by Hal Moore and his troops.

Moore dramatized the fate of the isolated Platoon 2, Company B, 1/7 Battalion in We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young, pp 76-77, 103, 138, 165-66, 206, 208, 209. Moore’s exaggeration had been corrected by

Retired Col. John Herren, another company commander in the battle, talked about the infamous "Lost Platoon" depicted in the book and movie.

"I want to make a point here -- it wasn't lost," he said. "Joe Galloway and General Moore, I don't know how you got that into the book. They were not lost; they were cut off.

"Now, they didn't know exactly where they were," he quipped, drawing laughter from the audience, "but that doesn't mean they were lost."

Herren offered the correction on May 2, 2012 Ranger Reunion in Fort Benning, GA.

Moore made the situation on the field to appear “hotter” than it really was when he mentioned about the call of Broken Arrow code made by Lieutenant Charlie Hastings, the forward air controller, around 7:00 am of November 15 We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young, page 175, as if his units were about to be overrun by the enemy assaults:

“I [Charlie Hastings] used the code-word ‘Broken Arrow’, which meant American unit in contact and in danger of being overrun – and we received all available aircraft in South Vietnam for close air support. We had aircraft stacked at 1,000-foot intervals from 7,000 feet to 35,000 feet, each waiting to receive a target and deliver their ordnance.”

Moore described the situation around that time in a calmer manner in his 1/7 AC After Action Report:

The enemy fire was so heavy that movement towards or within the sector resulted in more friendly casualties. It was during this action at 0755 hours that all platoon positions threw a colored smoke grenade on my order to define visually for TAC Air, ARA and artillery air observers the periphery of the perimeter. All fire support was brought in extremely close. Some friendly artillery fell inside the perimeter, and two cans of napalm were delivered in my CP area wounding two men and setting off some M-16 ammo. This we accepted as abnormal, but not unexpected due to the emergency need for unusually close-in fire support (50-100 meters). C Company, with attachments, fought the massive enemy force for over two hours. At approximately 0910 hours, elements of A Company, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry began landing.

It was also around that time that Colonel Brown decided to land down on LZ X-Ray, knowingly quite well it was safe, contrary to Moore’s indication that the situation was unsafe (Moore, page 202):

Mid-morning, before Tully arrived, Colonel Tim Brown flew in for a visit. Plumley recalls: “Lieutenant Colonel Moore saluted Brown and said, ‘I told you not to come in here. It’s not safe! Brown picked up his right collar lapel and waggled his full colonel’s eagle at Moore and said, ‘Sorry about that!”

Because of his misinterpretation of his secondary role, Moore was upset that his battalion was ordered out when this battle was not over and clung on to the command of his battalion so that he got to be “the first man of my battalion to set foot in this terrible killing ground and I damned well intended to be the last man to leave.”

Moore dramatized the situation in the early morning of his battalion’s withdrawal day, November 16 with the execution of a Mad Minute recon by fire (Moore, page 223):

At precisely 6:55 am every man on the perimeter would fire his individual weapon, and all machine guns, for two full minutes on full automatic. The word was to shoot up trees, anthills, bushes, and high grass forward of and above the American positions. Gunners would shoot anything that worried them.

The real situation on the enemy’s side was that the troops of the 7th and 9th Battalions of 66th Regiment facing the Air Cavalry troops at LZ X-Ray were in shock and demoralized by the thundering waves of B-52 carpet bombing raining down nearby since 1600 hours the previous day November 15 (General Nguyen Huu An’s Memoire):

By noon, we paused on the south side edge of Chu Pong mountain. I was standing leaning on a cane and was studying the surrounding terrain and not paying attention to anything else, when suddenly Dong Thoai lay down and pulled my foot. At that moment, a string of bomb exploded, running past our location.

- I said jokingly to Dong Thoai:

- Standing up or lying down at this location, you are merely at the mercy of luck.

My eyes followed the clouds of gray smokes that were dissipating, leaving a long trail along the mountain edge, with trees spilled all over. Way back when I was up in the North, I had read may documents pertaining to the American military machinery. And now, I saw it with my own eyes and was facing it. One B.52 transported 25 tons of bombs. Just for today, they used 24 planes taking turn circling over this Chu Pong area.

On that day of November 15, the carpet bombing was aimed mainly at the positions of 32nd Regiment, located about 12 kilometers northwest of LZ X-Ray (Pleiku Campaign, page 88):

Neither has there been an explanation for the failure to commit the 32d Regiment which apparently held its positions 12-14 kilometers to the northwest on the north bank of the Ia Drang.

The expenditure of ammunition in that two full mad minute firing of individual weapons and all machine guns resulted in the dead of merely two enemy snipers dangling on trees. (Moore, page 224)

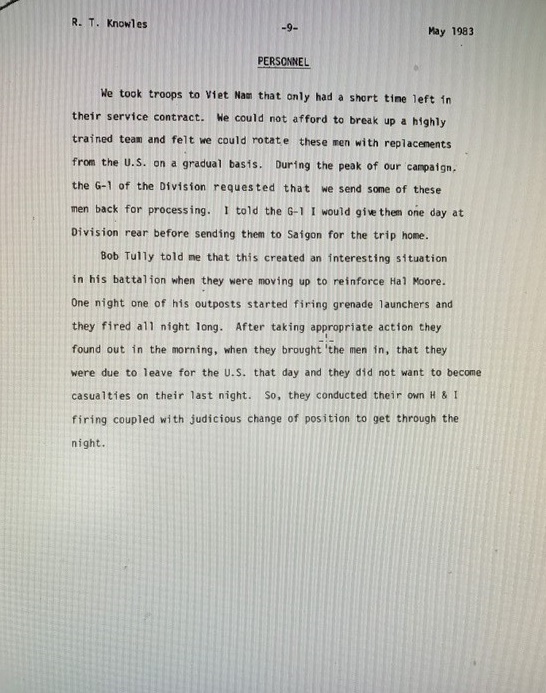

General Knowles characterized the "mad minute" action as a mere precautionary measure taken by the troops who were about to leave the country that day and "did not want to become casualties on their last night" :

In comparison to the main action conducted by the Arc Light operation, his secondary action weighed much less in time (2 days –November 14-15 versus five days – November 15-19), space (LZ X-Ray versus the entire Chupong-Iadrang complex areas), units committed (1/7, 2/7 and 2/5 Air Cavalry Battalions versus the B-52 fleet stationed at Guam), enemy forces engaged (2 NVA battalions versus 3 NVA Regiments).

LTC Moore wanted to convey the image of a valiant cavalier charging in a menacing enemy front line and fencing his way out of a hostile surrounding enemy circle in being the first man of his battalion to ride in LZ X-Ray in the first wave of air assault and the last man of his battalion to leave the landing zone. The reality was the scenario of a leisure ride in and out a park, both times without any incident and any single shot from the enemy. LTC Moore set his foot on LZ X-Ray at 10:48 am; the first shooting of “moderate intensity” exchange by lead elements of Company B, moving out of defense perimeter on patrol, with the enemy only occurred at 12:45 pm. The helilifted withdrawal of 1/7 Air Cavalry Battalion was conducted smoothly under the cover of 2/7 and 2/5 Air Cavalry Battalions.

Medal Awards of Gallantry Acts

It is quite surprising that such an epic battle as described by LTC Hal Moore in We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young did not generate many acts of gallantry officially recognized by medals: the Distinguished Service Cross for Colonel Hal Moore on June 1, 1966; the Medal of Honor for Second Lieutenant Walter J. Marm, Company A, 1/7 Battalion on February 15, 1967; the Bronze Star with Valor for Specialist 4 Gaelen Bungum, Company B, 1/7 Battalion (date awarded unknown); the Silver Star for Second Lieutenant John Lance Geoghegan, Company C, 1/7 Battalion (date posthumously awarded unknown); the Distinguished Service Cross for Staff Sergeant Clyde E. Savage, Squad 3 leader and Specialist 5 Charles R. Lose, platoon medic, both of Company B, 1/7 Battalion; the Silver Star for Major Bruce Crandall and Captain Edward Freeman, both pilots of Company A, 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion (date awarded unknown) .

In 1992, Moore and Galloway draw the attention to the oversight in their book We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young (New York: Random House, 1992, p. 374):

I had been pushing my staff hard as we wrote letters of condolence to the families who had lost loved ones killed in action and prepared recommendations for medals and awards. We had problems on the awards: We had few who could type, so many of the forms were scrawled by hand by lantern light. Many witnesses had been evacuated with wounds or had already rotated for discharge. Too many men had died bravely and heroically, while the men who had witnessed their deeds had also been killed. Uncommon valor truly was a common virtue on the field at Landing Zone X-Ray those three days and two nights. Acts of valor that on other fields, on other days, would have been rewarded with the Medal of Honor or Distinguished Service Cross or a Silver Star were recognized only with a telegram saying “The Secretary of the Army regrets ...”

It caught the attention of the Congress and in 1996 a law was signed that waived the three year report limitations required for the award of medals, including the Medal of Honor, pertaining to operations in the Ia Drang Valley, near Pleiku, South Vietnam, from October 23, 1965, to November 26, 1965 (Barbara Salazar Torreon, Medal of Honor: History and Issues, August 18, 2015). This signed law allows any member of Congress to submit medal recommendations for past wars for military award boards to consider.

Undoubtedly, all the surviving veterans of the Ia Drang Valley battle have been contacted and solicited to joint efforts in this search to correct the oversight. The results, though, turned out to be pretty disappointing: in 1996 Specialist 4 Bill Beck and Specialist 4 Russell E. Adams (Platoon 3, Company A, 1/7 Battalion) were awarded the Bronze Star with Valor; on May 1, 1998, Galloway was decorated with the Bronze Star with Valor in recognition of his bravery at the Battle of Ia Drang; Captain Edward Freeman and Major Bruce Crandall had their Silver Star medals upgraded to Medals of Honor in 2001 and 2007, respectively.

In brief, after two decades of painstaking search, only three additional acts of gallantry with Bronze Star medals were unearthed about the Ia Drang battle at LZ X-Ray, none at LZ Albany.

Nguyen Van Tin

29 January 2016

- Operation Pleime-Chupong B-52 Strike?

- The Use of B-52 Strike in Ia Drang Campaign, General Westmoreland’s Best Kept Military Secret

- Air War Over Pleime-Chupong

- Arc Light over Chu Pong Operation

- Catching a Thief Tactic in Pleime Campaign

- Pleime/Chupong Campaign Destroying B3 Field Front Base

- The Uniqueness in Pleime Counteroffensive Operational Concept

- Pleime Counteroffensive into Chupong Iadrang Complex

- The Unfolding of Strategic and Tactical Moves of Pleime Campaign

- Battle of Pleime

- The Truth about the Pleime Battle

- Intelligence Gathering at Ia Drang

- Intelligence, the Key Factor in the Pleime Campaign's Victory

- Roll Call of Combatants at Pleime-Chupong-Iadrang Battlefront

- "Victory at Pleime" ?

- Tactical Moves in Pleime Battle

- Kung Fu Tactics at Pleime Campaign

- Various Diversionary Moves in Support of Arc Lite Strike in Pleime Counteroffensive

- What if there was no master plan for Pleime Counteroffensive?

- Pleime/Chupong Campaign Destroying B3 Field Front Base

- A Few Things You Should Know about Pleime-Iadrang Campaign

- Things the VC Don't Want People To Know at Pleime Battle

- Reviewing "Why Pleime"

- Review of "Intelligence Aspects at Pleime_Chupong Campaign"

- Perplexing Maneuvers at Pleime-Chupong-Iadrang You Might Be Attempted to Question

- A Bird’s-Eye-View of Pleime Campaign

- Operation Dan Thang 21

- US Air Force’s Roles in Pleime Campaign

- Arc Lite Operation Planning and Execution in Pleime Offensive

- A Doctrinal Lesson on the Use of Arc Lite in Pleime Counteroffensive

- Command and Control of Arc Light Strike at Chupong-Iadrang

- A Military Genius in Action at Pleime-Chupong-Iadrang Battlefront

- Command and Control Skills in Pleime Campaign

- Behind-the-scenes Activities at Various Allied Headquarters During Pleime Campaign

- The Two Principals Players Of Pleime Chess Game

- Pleime Battle's Diary

- Pleime Campaign and Pleiku Campaign

- A New Look at Ia Drang

- Operation Long Reach

- LZ X-Ray Battle (General Knowles)

- My Contributions to the Battle of Ia Drang in Wikipedia

- Operation LZ X-Ray

- Colonel Hal Moore’s Self-Aggrandizement in “We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young”

- Colonel Hal Moore Misunderstood his Mission at the Ia Drang Battle

- What Historians Failed to Tell About the Battle at LZ X-Ray

- Hal Moore and 1/7th Air Cavalry Battalion's Real Mission at LZ X-Ray

- Two Different Narrations of LZ X-Ray Battle by II Corps

- Ia Drang Valley Battle? Which One?

- LTC Hal Moore Summoned to a Woodshed Session?

- Colonel Hieu's Operational Concept for LZ X-Ray

- LZ Albany Battle - Chinese Advisors' Perspective

- A Puzzling Air Assault Performed by 1/7 Air Cavalry at LZ X-Ray

- Two Different Narrations of Than Phong 7 Operation by II Corps

- General Schwarzkopf's Naďveté In Ia Drang Battle

- Venturing into Lion's Den in Ia Drang Valley

- American Perspective of Pleime Battle

- General Kinnard's Naďveté in Pleime Campaign

- "No Time for Reflection at Ia Drang" ?

- Pleime Campaign or Pleime-Ia Drang Campaign?

- A Critique of General Bui Nam Ha's Opinions about Plâyme Campaign

- Commenting on General Nguyen Huu An's Account of Plâyme Campaign

- Crushing the American Troops in Western Highlands or in Danang?

- What Really Happened at Ia Drang Battle

- Case Study of a Typical Misinterpretation of Ia Drang Battle

- Ia Drang Battle Revisited

Documents

- Why Pleime

- Pleime, Trận Chię́n Lịch Sử

- Pleime Battle Viewed From G3/I Field Force Vietnam

- Long Reach Operation Viewed From G3/I Field Force Vietnam

- LZ X-Ray Battle and LZ Albany Battle Viewed From G3/I Field Force Vietnam

- Than Phong 7 Operation Viewed From G3/I Field Force Vietnam

- Arc Light Strike at Chupong-Iadrang Viewed From G3/IFFV

- Pleiku Campaign

- Intelligence Aspects at Pleime_Chupong Campaign

- Excerpts of General Westmorland’s History Notes re: Pleime-Chupong-Iadrang Campaign

- LZ X-Ray Battle (General Knowles)

- LZ X-Ray After Action Report - LTC Hal Moore and Colonel Hieu

- Than Phong 7

- 52nd Combat Aviation Battalion in Support of Pleime Campaign

- CIDG in Camp Defense (Plei Me)

- Viet Cong Requested Red China's Aid

- Battle of Duc Co

- NVA Colonel Ha Vi Tung at Pleime-LZ Xray-LZ Albany

- The Fog of War: The Vietnamese View of the Ia Drang Battle

- No Time for Reflection: Moore at Ia Drang

- 1st US Cavalry Division Gives Support in the Battle at Plei Me

- Plei Me Fight Stands As War Turning Point

- Plei Me Battle

- Seven Days of Zap

- Pleime Through New York Times' View

- First Engagement With American Troops at Pleime-Iadrang

- Pleime Campaign

- Crushing the American Troops in Central Highlands

- NVA 66th Regiment in Pleime-Ia Drang Campaign

- The Political Commissar at the First Battle Against the Americans in Central Highlands