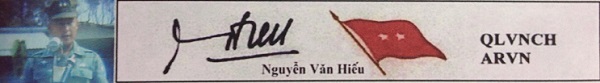

General Nguyen Van Hieu

We are about to touch upon a nagging hidden spot – a deep resentment which started since the days in March, April 1975 – caused by the loss of country and dwellings, the existence of an expatriated, of humiliation that could not be restored, and that one could not find an explanation… Why? Because of whom?! Then, each individual had to draw from his/her situation, a rationalization of his own in responding to these stern questions. Why did it come to this? Why must one bear this tragic situation? Then we all kind of console one another in accepting that this is common suffering that the Vietnamese people as a whole have to embrace. But in this tragedy that the country was contemplating at the moment of agony, there was one man, a whole family that had to endure the resentment earlier and deeper, sooner than when South Vietnam collapsed: General Nguyen Van Hieu’s family – the General who was cut down at the same time the nation lapsed into total annihilation.

We are going to relive the unjust fate of the General and the unfortunate destiny of the Nation – April 8, 1975 – Thirty years ago, when South Vietnam collapsed, and also the day our Loyal, Courageous Soldier was harmed by dark devilish elements.

I. The Beginning of a Saga

In 1949, when the Red Army was about to take control of entire China, young Nguyen Van Hieu who had just reached twenty years old, left Shanghai with his family, from the French concession to repatriate to Saigon. From there, he moved up to Hanoi, because his father, Mr. Nguyen Van Huong, a high ranking official in the security and national intelligence at its formation phase in the fifties, was nominated Deputy Director of Northern Security. With the wide connections and position of his father in the political milieu, coupled with a high level of education (student in technology at Aurore University run by the French Jesuits) and his proficiency in English, French and Chinese, young Nguyen Van Hieu would have no difficulty and plenty of opportunity to pursue high level of education in advanced institutions in Europe and United States, a general trend in the beginning of mid 20th century (after WWII); furthermore, the number of students applying to study overseas was very low at that time. Nevertheless, he chose to follow a different direction, an uncertain path, more dangerous – the military career of a combat soldier. In 1950, he entered Class 3 of the Dalat Inter-arms Military Academy, one of the first classes after the Military Academy was transferred from Dap Da (Hue) up to Dalat to form the leadership cadre of the National Army. Such was the army with its officers that would carry out the heavy burden of a war between Nationalists and Communists that lasted three decades with a tragic outcome on April 30, 1975. Young Nguyen Van Hieu – General Nguyen Van Hieu, indeed went through the war that devastated the country without respite, and ended up at the same time as the unfortunate destiny of his country. We have the task of recounting the entire journey of his combat life – the General who lived, fought and died with the destiny of the country – for, the next generation’s history of the nation must reckon one great fact: the Soldier of the Republic of Vietnam was the entity that had performed the task of Defending the Nation and Protecting the People, despite the destiny of the country which was entering its decadent phase, with the lot unjustly imparted to the soldiers through the defeat on April 30, 1975.

General Hieu epitomized the stoical attitude and unselfish spirit of an ARVN soldier. His death, although it was a tragic ending, nevertheless equally shed further light on an extremely noble heroic figure.

The military career path of Soldier Nguyen Van Hieu commenced with first uncertain steps that were not smooth by all means, although our 3rd Class Cadet of Dalat Inter-arms Military Academy possessed all the excellent abilities necessary to accomplish the training program with the highest scores. He was the officer cadet who had the highest scores in academic subjects, the highest scores in military subjects, equally the highest scores in behavior (côte d’amour) due to his amenability, his modesty, his helpfulness toward classmates, his respect toward rules and principles – a model suitable of a military life; in other words, young men whose mind and body were molded in view of becoming Commanders who would lead troops into the battlefield; men such as De Gaulle, De Lattre, Bigeard of the French Army, Montgomery of the British Army, Rommel, the Fox of the German Army, or the Great Soldier of the American Army, McArthur. Lieutenant Nguyen Van Hieu graduated 2nd of his Class, relinquishing the honor of 1st Rank to Lieutenant Bui Dzinh because Emperor Bao Dai had expressed his desire of having a cadet originated from Center Vietnam to hold that position of honor. Lieutenant Nguyen Van Hieu did not hold a grudge – he was confident of his abilities – with the confidence of a Combatant coupled with the self-respect of an Oriental Scholar. His exceptional later life would prove the veracity of these high qualities of this beginning phase.

The next misfortune was caused by tuberculosis due to catching a cold during a physical exercise conducted under the rain (another caused might also be hereditary since his mother also had died of tuberculosis). This might be the reason for our young lieutenant to slump into depression when he listened to a classmate, Captain Lu Lan, recounting his military feats in the Quang Tri battlefield (which had allowed this classmate to be on a fast track in term of promotion to the rank of captain). “Look, I am a handicapped know, I wonder what my future will turn out to be?” But this feeling of depression at the bedside in Lanessan Hospital (Hanoi) was only temporary, and Lieutenant Hieu, unlike the majority of soldiers who contracted tuberculosis – since military career demanded physical stamina, and furthermore at the beginning of the second half 20th Century, the anti-dote to this disease was still rare – often seized the pretext for an honorary discharge. On the contrary, after a period of convalescence, he went to the South, and continued his military career with a renewed attitude and a new position as a general staff officer under Chief of Staff, Colonel Tran Van Don, as a G3 officer (Operational Center, Training – the most important section in the general staff organization of all modern armies), Captain Nguyen Van Hieu’s skills were allowed to blossom entirely, in preparation for later positions of high command and general staff. For this reason, when Colonel Tran Van Don was promoted to Major General and was assigned I Corps Commander (Military Region I, from Quang Tri to Quang Ngai), he brought with him this excellent general staff officer to Danang. In 1971, when this general staff officer was summoned to appear on the floor of Congress to be questioned about the defeat in the withdrawal out of Snoul City (Kampuchea), Senator Tran Van Don, Chairman of the committee overseeing the Defense Department at the Senate, had this statement to say: “If the ARVN had more generals as competent as General Hieu, Vietnam would not have been lost”. This statement was not a mere subjective endorsement but was based on proven facts. Let us examine some typical military exploits to back up this assessment.

II. Amid Battlefield

Even though military historians have divergent opinions (even American officials, scholars who had unjustified prejudgment toward the Army of the Republic of Vietnam), nevertheless all had to agree one thing: General Do Cao Tri was the best tactician of the army of South Vietnam, of entire Vietnam (if one compares him with the generals of North Vietnam); and not so much less than the famous generals of allied armies. But perhaps, the majority of them would lack accuracy in not finding out one of the reasons behind the military exploits of famous General Do Cao Tri. This reason existed since the days he held the position of 1st Infantry Division Commander (before the 11/11/1963 coup) when he entrusted Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Van Hieu the position of 1st Division Chief of Staff. The close relationship between these two fine combatants lasted a decade (60-70), and only ended when General Tri died in a helicopter accident on 2/23/1971, before he was about to leave the position of III Corps Commander (Bien Hoa) to go to Danang to replace General Hoang Xuan Lam at the moment the battle in Laos (Operation Lam Son 719) was in critical situation. General Do Cao Tri only consented to accept the Command of I Military Region if the person who replaced him as III Corps Commander had to be (and nobody else): General Nguyen Van Hieu, 5th Infantry Division Commander (Binh Duong) – the attack spearhead that had created the Binh Tay Victory – the Campaign that defeated the Southern Central Command starting at the end of 1969. Something deeper than military task must have been the link that jointed these two exceptional military geniuses together. The following military feats will be a clear explanation for this excellent collaboration between a fearless commander and an outstanding chief of staff. It also rectifies one thing: General Do Cao Tri had never been someone who “discriminated Southerner-Northerner” as rumor believed; on the contrary, he was the one that “protected” General Hieu to the end. Similarly, General Hieu could only fulfill his thorny task in the Anti-corruption Committee, if he was not backed up by a Southerner – a pure Southerner Official who loved, respected, protected him: Mr. Tran Van Huong.

1964. Do Xa

Do Xa stronghold of the communist force nested in the mountainous area at the junction of the two Provinces of Kontum and Quang Nghia, according to the regional determination of the Republic of Vietnam; or it belonged to the operational zone of Communist Battle Fronts B3 and B5. It was the most treacherous area of the Annamite Mountains right at peak Ngoc Linh, (8,524ft), dominating the entire Lower Laos region, leading down to the delta of the coastal region of Center Vietnam belonging to the two Provinces of Quang Nam and Quang Ngai, and it constituted also the path leading to Kontum, Pleiku of the Western Highlands. It was put under the command of General Nguyen Don and was an impenetrable area since the Indochina wartime of 1945-1954. During the 2nd Indochina War (1960-1975), since he was appointed I Corps Commander (Danang), General Tri intended to “visit” this forbidden location, but he did not have sufficient force to launch a big operation (especially lacking tactical air support and troop transport helicopters); furthermore, social-political unrest during the entire year of 1963 forced him to abandon the idea to clear up Do Xa stronghold. In 1/1964, General Tri took over the command of II Military Region, the “sticking bone” of Do Xa came back as a challenge, and this time he decided to act, although the majority of this operational area was set in the area of Quang Ngai Province (belonging to I Military Region). Colonel Nguyen Van Hieu, II Corps Chief of Staff, was entrusted the task of designing and executing the operation which was put under the command of I Corps Commander, Major General Do Cao Tri, and Colonel Lu Lan, Operational Deputy Commander. The operational force was divided into two groups: Group A comprised three Rangers battalions under the command of Major Son Thuong; Group B consisted of 50th Infantry Division under the command of Major Phan Trong Chinh which was the main thrust of the operation; it was reinforced by 5th Airborn Battalion of Major Ngo Quang Truong. With his wide connection since the days he was in charge of operations in I Corps, Colonel Hieu had established a close relationship with Major Wagner, USMC Advisor to I Corps HQ; and together with Major Wagner, they became the main factors in the coordination of the troop transport plan by helicopters. USMC HMM-364 Squadron with 16 helicopters H34 ferried the troops et debarked them at the same time on the landing zone, reinforced by two AFVN helicopters H34 coming from Danang. They were escorted by five UH-1B armed helicopters belonging to US Army 52nd Aviation Battalion “Dragon Flight” all along with the flight and at the Do Xa landing zone (LZ). The operational zone was covered by the observation plane L19 US “Bird Dog”; furthermore Helio Courier STOL plane of Colonel Merchant, from the CIA and Colonel I Corps Senior Advisor circled at 5,000 feet to monitor the entire operation (USMC knew this operation under the name of Sure Win 202). Based on the above-mentioned facts, Operation Quyet Thang 202 was not merely a pure military activity but was testing of ARVN’s capabilities after the political turmoil of 1963, and specifically was aimed at assessing the capabilities of high ranking officers that were commanding and executing this operation.

On April 27, 1964, the Do Xa campaign was launched. From Quang Ngai airport, where the Operational Forward HQ was set up, 18 helicopters H34 of the first attack wave ferried the entire 5th Airborn Battalion to the battleground. Enemy anti-aircraft batteries were not only positioned around the landing zone, but they were also set up on top-hills along the paths followed by the troop transport helicopters. Let us listen to the account narrated by Captain “Woody” Woodmansee, leader of the helicopter gunships (nowadays a retired US Army Lieutenant General), “On the first pass, low level at about 100 feet, all of my first four Dragon guns were throwing smoke out both sides of the aircraft. I could see tracers crisscrossing the valley from both sides (only one out of five rounds were tracers). On one of my passes west to east, I was engaged by a 50 cal. from the south side. There was a stream of tracers passing about 10 feet under my helicopter for at least 10 seconds.” Such was the scene in the air. On the ground, 5th Airborne Battalion was attacked right at the landing zone. Major Ngo Quang Truong deployed all four combat companies and the Command Company to face the enemy. Company Leader Tran Dai Tan Au was killed right at the moment his foot touched the ground at the landing zone; the 57 cal. recoilless machine gun of Headquarters and Headquarters Company (normally used to destroy bunkers and tanks) now was transformed into a direct firearm to defend the immediate perimeter of the battalion command post. General Tri personally commanded the battle from the air; the helicopter which carried him, General Lu Lan, General Minh (later AFVN Commander) had to fly at treetop level to avoid anti-aircraft gunfire; but when it returned to Quang Ngai airport, an examination showed that its flanks and bottom were pierced by several bullets. Without feeling any setback, General Tri sent in the rest of Rangers units into the battleground, to join in with the airborne units in an operational sweep of this impenetrable stronghold named Do Xa. Just in the second day into the operation, the Rangers only had captured a 30 cal. heavy machine gun, a light machine gun, 11 AR-15 rifles, six submachine guns and 144 individual weapons, 1,000 heavy detonators plus a great number of grenades, mines, ammunition, documents, and military equipment. At the end of the operation, the total amounts of weapons counted two additional 52 mm caliber machine guns, one 30 mm caliber machine gun, 69 individual weapons with 62 enemies killed and 17 captured. The operation ended exactly a month later, on May 27 with the 50th Infantry Regiment of Major Phan Trong Chinh having swept the entire Do Xa area while the Airborne and Rangers units were establishing peripheral blocking positions which interdicted enemy forces to escape into the western mountainous areas or toward the south of Highlands.

The number of weapons captured and the enemies killed did not constitute a major military victory, but from a political standpoint, it had proved one thing: After the political turmoil (1963-64) in which the whole army had been swirled in by some individual military leaders who wanted to snatch the power of the nation according a trend which championed “Military authority with the power of the gun” in vogue all over the world (Nasser in Egypt, Pak Chung Hy in South Korea, Fidel Castro in Cuba, and nearby in the Indochina region, Captain Kong Le in Laos, etc), the ARVN had regained combat strength; it was capable of conducting big operations at regimental and divisional levels when general staff officers and commanders received adequate supports, in particular when they were given full authority in the deployment of troops based on battlefield’s reality rather than on a display with a political agenda. An evidence which supports this interpretation lies on Operation Phi Hoa with hundreds of troop transport helicopters (the biggest troop transport by helicopters, mobilizing helicopters from entire Southeast Asia) and with the involvement of four airborne battalions being dropped at once in the Ho Bo sanctuary (Binh Duong) in the end of August, 1964. This operation did not produce the anticipated desire. Or on this same Do Xa battleground, General Nguyen Khanh and his Chief of Staff Ngo Dzu, once had failed before they swapped positions with General Do Cao Tri and Chief of Staff Nguyen Van Hieu respectively. Finally, all had shown that Operation 202 of II Corps into Do Xa was a well-designed plan, responding to the situation and demand of the battlefield, was commanded and executed by competent strategists and tacticians with determination: Attacking with a sure win, not as troop display betting on soldiers’ lives. Furthermore, one detail needs to be mentioned: airborne, rangers and infantry units in Do Xa battle, all were commanded by officers originated from airborne branch: General Do Cao Tri, Majors Phan Trong Chinh, Ngo Quang Truong, Son Thuong – But all had relied on Colonel Nguyen Van Hieu’s planning and strategic skills. This is also the purpose of this task which is although belated, nevertheless essential that we must do today toward a Soldier who had died in the hand of a regime composed of immoral, corrupt, power-hungry, blood-sucking leaders. The following will prove this Common Suffering will lead to the painful collapse of April 30, 1975.

1965. National Route 19, An Khe Pass – National Route 14, Duc Co; Pleime

07:00 pm June 24, 1954, only less than six months later (June 20, 1954) the Geneva Accord would be signed, ending the First Indochina War. But on Mang Yang Pass, at Kilometer 15th, on National Route 19 linking Pleiku (Highlands Military Capital) with Qui Nhon (the most important seaport of Center Vietnam), an infernal scene was unfolding. 803rd Regiment NVA attempted to annihilate the entire Korea Regiment of the French Expeditionary Army, a unit whose feat was to stop the human waves of the Communist Red Army on the Korea battlefield in 1952, along with US 2nd Infantry Division. That was why soldiers of this regiment still wore on their shoulders the insignia boring a White Star with the Head of an Indian of this famous unit. But now, in 1964, it was An Khe Pass of the Vietnam War and no more the Korea peninsula of 1953. The remaining combatants of the 100th Mobile Task Force (of which the Korea Regiment was the assault element, the pride of the task force) were trying to regroup after being decimated by a six-hour close combat with Communist units. In reality, they had endured six months of devastation since they got involved in this Highlands battleground. Nighttime came down quickly although the sky of this mountainous region in June was enlightened by illuminated grenade explosions thrown by soldiers to destroy artillery batteries, to burn up equipment, to use up heavy machine guns in preparation of an escape of the encirclement by 803rd Regiment NVA. (Bernard B. Fall, Street Without Joy. Schocken Books - New York, 1972 pp 214-220). To put it bluntly, the battle of An Khe Pass on National Route 19, with the total annihilation of 100th Mobile Group, was only the tactical aspect of an overall strategic plan: To isolate the Highlands, to occupy the route linking North-South, west of Annamite Mountains, along Route 14 down to Ban Me Thuat, to the upper end of Dong Nai River, and the eastern region of South Vietnam. This battle plan of 1954 would later be repeated in the years 1974-75 before the loss of South Vietnam with the Highlands territories leaving open, caused by the ill-fated refugee flow along Provincial Route 7 from Pleiku to Tuy Hoa of II Corps with the entire territorial force of this military region. But 1965 in the Highlands was different. Let us see how Colonel Hieu, II Corps Chief of Staff had lived and fought in the Highlands.

In 1965, North Communists launched a campaign aiming at slicing Viet Nam in two pieces, from Highlands down the coastal region along Route 19 by defeating the ARVN in conventional warfare. At this point, we have to use “North Communists” because the forces that participated were regular units belonging to B3 and B5 battlefronts, commanded by the North Vietnam Military General Directorate with a facsimile of 1954 Dong Xuan campaign as described previously. National Route 19 and Mang Yang Pass once more were inflamed. On February 20, 1965, Forward Operational Outpost #1 of a Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) Company on Route 19, west of Mang Yang Pass, was attacked after a Regional Force Company was ambushed while moving from Pleiku back to a camp at Mang Yang Pass. Both the Regional Force Company and the CIDG Camp were not capable of facing the Communist regular forces, because these units were equipped with the latest models of Russian weapons: AK machine gun, RPD grenade-launchers, and an improved replica of anti-tank rockets RPG2. Meanwhile, the CIDG, Regional Forces, or ARVN units like Paratroopers, Rangers, Marine Corps, (in 1965, 66, 67…) still used antiquated weapons from WWII such as Garant, Carbin M1, etc. The battles along Route 19, on the two western and southern sides of Mang Yang Pass, repeated the typical tactics applied (and applied with success) by the Communist side – “Attack the Post and Ambush the Relief Column”. However, after two days of fierce fighting, CIDG #1 (West of Mang Yang Pass) and CIDG #2 Camp (East of Mang Yang Pass) still held with the help of rotational supports; they also received relief from a Rangers Battalion garrisoned at An Khe (50 kms East of Mang Yang Pass) which constituted a reserved force. The Special Force Command Post in Pleiku had also created CIDG companies specialized in helicopter intervention groups using Eagle Tactics when needed. Although caught off guard by helilifted troop transport tactics, with close firepower supports provided by US armed helicopter gunships, AFVN Skyraiders, and B27, enemy anti-aircraft system was very sophisticated and efficient, causing great damages to CIDG, Rangers, and Eagle flight units. By February 24, the situation reached a critical point: Forward Operational Camp #2 of CIDG (with an added element of Rangers stuck behind) needed to be evacuated because they could no more sustain the pressure of continuous mortar pounding coming from 83mm mortars positioned tightly around the camp. Among the 220 soldiers that needed to be evacuated was a wounded 9-month-old baby, the sole survivor among the passengers of a civilian bus going from Qui Nhon to Pleiku that had been massacred the day before when the vehicle entered the enemy artillery grid.

Colonel Chief of Staff Nguyen Van Hieu and US II Corps Senior Advisor, after two days ofmonitoring and studying the battlefield reached a common conclusion: enemy forces were regular battalions of Battle Front B3 equipped with modern weapons; they were efficient in mobile firepower and anti-aircraft concentration tactics. This army showed clear signs that it intended to joint force with the army from the delta (Binh Dinh region-Military Zone 5 NVA) to transform An Khe valley (East of Mang Yang Pass, along Route 19) into a huge battleground, aiming at cutting South Vietnam into two pieces as they had done in the 1945-1954 war. And the urgent measure was to pick up immediately the troops encircled in Camp #2 before it would be engulfed. General Nguyen Huu Co, the newly appointed Corps Commander, agreed in principle but raised a dilemma: lack of sufficient firepower to cover the area in support of the helicopter operation aiming at picking up the troops at Camp #2; furthermore, the network of enemy 82 mm mortars around the camp would create a pool of flames at the landing zone (within the camp). Under such conditions, the helicopter operation would become a suicidal attempt. Finally, III Corps resorted to adopting General Westmoreland’s decision: to use US F-100s jets together with ARVN A-1E and B57 in close strafing along the two valley sides, while helicopter gunships flew shotgun at motors positions near the camp, allowing transport helicopters to enter the landing zone to pick up troops. This helicopter operation was designed and executed like a miracle. No one was hurt in the first three lifts, only one helicopter was hit and one soldier was wounded in the last lift. Colonel Chief of Staff Nguyen Van Hieu had succeeded a rescue operation designed by him with smooth coordination between US and VN units, a feat not known by many until these days.

After the relief of CIDG camp, II Corps Command called up the reserved force: 2nd Airborne Task Force comprising two Battalions, the 7th, and the 8th, was helilifted from Saigon and disembarked at An Khe airport; from here, they launched a sweeping operation along the entire thorny stretch from An Tuc District to Mang Yang Pass. Feeling outsmart, the enemy switched north and attacked K’nack Special Force camp (North of Route 19 to alleviate the pressure exerted by the paratroopers at An Khe valley) with human waves (similar to Red Communist Army’s tactics used at hilltops Pock Chop, T-Bone and Old Baldy in the Korea battle in 1953): two battltions gave assault at outpost manned by merely a CIDG platoon. An outpost was overrun but was retaken by a CIDG counter-attack, supported by paratroopers attacking from the south, which broke the enemy forces around the Force Special camp. At the end of the battle, the enemy withdrew leaving behind 126 dead, numerous 57 mm recoilless batteries, 82 mm mortar-launchers with lots of ammunition and explosives. But the major accomplishment of the operations was: convoys of trucks escorted to Pleiku instilled a renewed morale in the Highlands. Food and commodities prices dropped 25 to 30 percent, and the population regained a sense of security, confidence, and hope. Students in Pleiku volunteered in helping soldiers in unloading cargoes and people reverted to their homesteads. (General Vinh Loc, Military Review, April 1966) However, not many individuals among the population of Pleiku those days were aware that the life they had recuperated was the result of the sacrifice of hundreds, thousands of soldiers – Among them was the Great Soldier, extremely modest, totally dedicated to the army and the country – Colonel Chief of Staff Nguyen Van Hieu. Who among the population of Pleiku knew or heard of Him; even this writer, a young lieutenant belonging to the 7th Airborn Battalion, the unit that cleared the road between An Khe and Mang Yang Pass in March 1965.

After defeating the enemy at the battles on Route 19, II Corps Command launched a campaign to retake Bong Son, Tam Quan (April 1965) with 22nd Infantry Division reinforced by a Marine Corps Brigade in order to counter the enemy’s intention to cut National Route 1 around the tactical area of Quang Ngai-Binh Dinh (belonging to Battle Front B5 NVA) which forced the Communists Command in ARVN Military Region II to revise their plan. And once again, the Hanoi’s leadership reverted back to the battleground along National Route 14 (which linked Pleiku with Ban Me Thuoc to the south, with Kontum to the north, from the raining season to the beginning of the dry season (from April 4 to the end of 1975) with the most seasoned divisions of Battle Front B3: 325th, F10th, 2nd Golden Star Divisions, commanded by competent Generals Vu Lang , Hoang Minh Thao, Chu Huy Man (later, toward the end of the war, in February 1975, Chief of Joint General Staff Van Tien Dung in person commanded the campaign to control the Highlands under the direction of Hanoi General Directorate). Meanwhile, II Corps Command consecutively replaced its Commanders: General Do Cao Tri, Nguyen Huu Co, Vinh Loc successively held the position of II Corps Commander – while only the Chief of Staff remained at the same position. Therefore, we can make the assertion about a fact without being afraid of making an error, of being subjective: It was Colonel Nguyen Van Hieu, II Corps Chief of Staff who was the person who dealt continuously and directly against the military command of the North at the Highlands battleground during the entire year of 1965.

Beginning of the rainy season of 1965, along National Route 14, communist forces continuously launched systematic attacks as following: On May 16, Phu Tuc District and Buon Mroc belonging to Phu Bon Province (or Hau Bon, old name Cheo Reo), about 70 kilometers southwest of Pleiku, were attacked; the Regional Forces called the nearby Special Force Camp for help without success because that the Special Force unit was also attacked, both the rescue column and the camp. The situation at Phu Bon deteriorated rapidly, II Corps had to helilift one battalion of 40th Regiment/23rd Division to come to the rescue. Phu Bon Province could only communicate and be resupplied by air because Le Bac Bridge on Provincial Route 7 had been damaged. On May 20, the enemy attacked the Regional Force unit that guarded the Pokala Bridge and destroyed this important bridge, cutting off the entire network of outposts, Special Force camps located northwest of Kontum. The situation was getting worst entering May 1, when a delegation of Pleiku Province lead by the Province Chief on an inspection mission at Le Thanh District (30 kilometers west of Pleiku, on the left side of Route 14) was ambushed and the District was overrun early in the same day. II Corps had to deploy Eagle Flight teams to rescue the delegation and dispatch an airborne task force present in the region to rescue Le Thanh District. The situation did not end here, the rescue column met the chief of province’s delegation convoy at a location on National Route 19 (between west Pleiku and the Vietnamese-Kampuchean borders). This was also the ambush location set up by the enemy. Helicopter gunships of US Army 52nd Aviation Battalion from Camp Holloway had to continuously intervene to lend air support and to allow the delegation to withdraw. Two helicopters were shot down; the delegation convoy suffered heavy loss both in human beings and vehicles (including the relief column units), and the survivors disbanded and attempted to get back to Pleiku. Finally, General Vinh Loc, II Corps Commander, had to abandon the old Le Thanh District headquarters and moved it to a nearby location close to National Route 14 (near Pleiku) for easier support. However, he had to hold Duc Co outpost, the farthest remote outpost of governmental forces situated at the western end of Route 19, facing the Kampuchean border.

The situation in the south, at Phu Bon Province, was no better, a battalion of 40th Regiment/23rd Infantry Division on its way to Le Bac Bridge to establish security and to repair the bridge fell into an enemy ambush, and was forced to revert to Phu Tuc District to finally suffer the same fate of encirclement of the entire province. Next Thuan Man District, southwest of the province was also attacked and at risk of being overrun. Again the airborne task force was dispatched to join forces with the 40th Regiment in an attempt to rescue the besieged troops. The enemy attacked the mid-section of the airborne and infantry units formation, overran the artillery position and destroyed the convoy transporting ammunition supply to Thuan Man. Airborne battalions had to regroup in self-defense for the medevac of wounded combatants and ammunition resupply. II Corps Command was faced with a grim situation which was getting worse and worse with signs of enemy’s determination to conquer the Highlands in the rainy season becoming more obvious and was forced to request reserved forces from Saigon. A Marine Corps Task Force and an Airborne Task Force were dispatched to Phu Bon in an emergency. In no time Cheo Reo airport became the busiest airport in the Viet Nam War. US transport airplanes coordinated by II Corps general staff flew in continuously round the clock to ferry in troops. As soon it touched the ground, the second Airborne Task Force hurried up to enter the jungle to deflate the pressure imposed on the task force that was encircled at Thuan Man.

North of Pleiku, Toumorong District in the northwest part of Kontum was overrun beginning July. Because it was too remote and was not an essential military location, II Corps gave the order to retreat to Dakto District (Tan Canh) where the Command Post of 42nd Regiment was located. It was then the turn of Dakto District headquarters to be attacked (July 7); the 42nd Regiment Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Lai Van Chu was killed; the US Senior Advisor, Major John R. Black was gravely wounded while commanding the relief column. This situation of the regiment deteriorated after the death of LTC Chu; II Corps hastened to appoint Colonel Dam Van Quy 42nd Regiment Commander; the US Senior Advisor, LTC Thomas Perkins (who had worked with Colonel Quy in the past) was also dispatched up hastily to reinforce the US Advisory Team. A Rangers Battalion and the Marine Corps Task Force newly arriving in the region were helilifted to Tan Canh to join forces with 42nd Regiment to block the enemy in the northern part of Kontum.

While the military situation was exploding every single day in the Highlands, in Saigon military turmoils were also swirling rapidly: Military showdown on 9/12/1964 failed coup attempt on 2/19/1965, followed by counter-coup on 5/20. Governmental cabinets raced in and out with Phan Huy Quat, Tran Van Huong; Catholics and Buddhists took turned to occupy the streets, fighting and transforming Saigon into a battleground no less fierce than the one with guns up in the Highlands. Battles at Special Force Camps Duc Co, Pleime were like the last drop tipping of water out the glass at the same time corps commanders were replaced reflecting the military situation in Saigon. Only Colonel Hieu stayed put in the position of II Corps Chief of Staff by the sides of soldiers who stood fast amidst the flames ravaging the mountainous regions of the Highlands.

Duc Co Camp was located at the western end of Route 19, facing the Vietnamese-Kampuchean border. It was under the full pressure exerted by the enemy force of Battle Front B3 after Le Thanh District was overrun (as above-mentioned). By mid-July, the camp was tightly encircled and all patrols venturing outside the camp were beaten back in. And although hundreds of bombardment missions had been executed around the camp, enemy units conducted perfectly the art of underground warfare and had cleverly set up a network of mortar launchers around the camp, threatening the helicopters landing zone which became unusable. A bold military operation was designed with sophistication and precision by Chief of Staff Nguyen Van Hieu and submitted to II Corps Commander, using 1st Airborne Task Force comprising three Battalions, the 1st, the 3rd and the 5th , first rank assault units of the Airborne Brigade (prior to 12/1965, Airborne Division was not yet created) with the mission to take the earliest possible control of the airstrip (reserved for C123 and Caribou planes) after tactical bombers attacked enemy mortars position around the camp. After succeeding in landing on the airstrip as planned, the 1st Airborne Task Force attempted to widen the control perimeter failed, they had to revert to the airstrip. The challenge faced by II Corps General Staff was that the number of enemy troops engaged in the battle was much much superior to the number of Airborne combatants (merely a task force comprising three battalions which had been severely damaged by battles at Phu Bon, Cheo Reo areas since April); while the enemy forces encircling the camp numbered one regiment, which means the enemy had thrown in a division into the battleground. It was no more a matter of battles at battalion, regiment levels with a Special Force Camp as target, but rather a strategic intent of the entire battle of 1965 in the Highlands areas had clearly emerged : Hanoi’s army under the command of General Hoang Minh Thao was determined to take control of the Highlands and then poured down the coastal area, cutting South Vietnam in two along the ax Pleiku-Binh Dinh (The battle in March 1975 was merely a replica with some adjustments of this battle in 1965). Colonel Hieu submitted a great plan to the Joint General Staff: to request the American troops to replace ARVN units as reserved force and to assume the role of territorial security, allowing them to form an assault task force the size of a division in order to deal with the battleground at Duc Co (military textbook dictates that the attacking force cannot be less than 1/3 of the defending force). The plan was approved by General Westmoreland and he decided to deploy 173rd Airborne Brigade, with General Stanly R. Larsen as US I Field Force in Pleiku, to replace ARVN units with the task of support and territorial security. This relief allowed II Corps General Staff to establish a Task Force comprising 1st Armored Cavalry Regiment (M41 tanks, M8; Armored Personnel Carriers M113); a Rangers Battalion; Marine Corps Task Force with artillery and territorial artillery support. The rescue column force was put under the command of Brigadier General Cao Hao Hon, 24th Special Zone Commander (north Kontum).

On August 8, the task force entered the area; the forward unit encountered immediate enemy resistance, and one tank was knocked down by a recoilless gun upon veering from Route 14 into Route 19. The enemy adopted close contact tactics clinging close to the relief column to avoid artillery firepower and attacked at its center to cut the task force into isolated pieces. That night, the two rescue column sections regrouped and redistributed troop positions despite the fact the enemy launched a series of attacks and artillery poundings aiming at breaking the rescue plan. At dawn August 9, 1st Airborne Task Force poured out from Duc Co airstrip and attacked down Route 19 toward the east to link with the relief column force in anvil-hammer tactics. To avoid entrapment between these two attacking forces, the enemy retreated, leaving behind small delaying forces, snipers and mines along their paths. Duc Co battle ended with a heavy loss on the Viet Cong side. The governmental troops took control of the battlefield and the victory boosted the morale of the ARVN troops. They had sustained the worst the enemy could have imposed on them; not only were they able to stand fast, but they succeeded also in forcing the enemy to break contact and flee, leaving numerous weapons, dead on the battleground. (Colonel Theodore Mataxis – VC Summer Monsoon Offensive 5/1966). General Westmoreland and the Head of State, Lieutenant General Nguyen Van Thieu came to Duc Co to emphasize the importance of the victory. But Colonel Chief of Staff Nguyen Van Hieu did not get the time to catch his breath; he used the newly liberated camp as the command post to deploy troops in conquering the second objective: Special Force Pleime Camp. He stayed all night during the rescue mission of Pleime.

Before 10/1965, few people had heard of the name Pleime, a Special Force Camp located west of National Route 14, at a distance of 40 kilometers southwest. But suddenly, Pleime became notorious in the South Vietnam military history because, after the defeat in the attack of Duc Co, the enemy had “manipulated the reality – a necessary process after performing a tactical attempt, a political endeavor without consideration of the outcome, defeat or victory”. And with the lesson newly learned from Duc Co, they came up with the following plan: 1/ to encircle Pleime; 2/ to destroy the rescue column; after concentrating troops at Pleime in order to transform it into tactical point that weakened II Corps defense force in Pleiku, and finally 3/ to utilize the remaining regiment still intact to attack Pleiku with a three-prong directions (from north, along Route 14; from east along Route 19, and from southwest, the gate of Duc Co, Pleime). All these tactical moves were entrusted to General Chu Huy Man with 320th Division (Dien Bien Phu Division) comprising three Regiments, the 32nd, the 33rd, and the 66th, ever since the main forces in the Highlands region. In order to defeat the enemy plan, II Corps General Staff designed a counter-attack based on the following premises: 1/If Pleime was to be rescued, the rescue column would unavoidably fall into the ambush on its way to the camp (similar to what had happened when rescuing Phu Tuc, Thuan Man, and recently Duc Co, etc.); the defense of Pleiku would weaken; 2/If Pleime was left alone to its fate, then it would be a damaging blow to the morale of the entire Military Region II. Once more, General Westmoreland took a wise and efficient decision, which was to bring in an Air Cavalry Brigade from An Khe to Pleiku, under the command of General Stanly R. Larsen, to be the defense force of Pleiku, and reserve force of the operation. This brigade also deployed 155 mm and 105 mm artillery batteries to directly support the rescue column task force. This task force comprised 1200 troops placed under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Trong Luat, armor, comprising 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, 1st Battalion/42nd Regiment; two Rangers Battalions, the 21st, and 22nd. The task force was supported by combat engineer and artillery units. Furthermore, there were two Special Force companies belonging 91st Airborne Rangers Battalion (the predecessor of 81st Airborne Rangers) in coordination with Delta Project Team of Major Charlie A. Beckwith (US Special Force); on 10/20, they jumped in the area close to Camp Pleime, to become the assault force coming out the camp to link with the rescue column units of Lieutenant Colonel Luat as planned from Route 14 which advanced to the camp from the junction of Provincial 6C.

However, the rescue plan was not that simple. II Corps General Staff had drawn lessons learned from the Duc Co battle in August 8. On 10/23, 22nd Rangers Battalion, instead of being used as element accompanying armored vehicle units of LTC Luat, was dropped by helicopters at a spot south of the ambush location set up by 32nd Regiment/230 Division NVA in an anvil-hammer tactic. Although the battle on the 23rd and 24th had been prepared meticulously (by both sides), the military situation still changed at the most unexpected moment. 635th and 344th Battalions NVA belonging to 32nd Regiment NVA under the command of LTC Nguyen Huu An, from well prepared and camouflaged positions, moved in to attack the rear section of LTC Luat’s rescue column, causing heavy damages and succeeded in pinning down the forward units at 5 kilometers of Camp Pleime. II Corps dispatched artillery forward observers of the US Air Cavalry brigade to assist the relief task force. These forward observers coordinated precise close artillery poundings (from batteries of the US Air Cavalry), creating a carpet unfolding a step ahead of the slow advancing armored vehicles. Furthermore, US F-100, helicopter gunships and AFVN AD1 using precise firing techniques set up a firepower fence protecting the flanks of the relief column. The excellent coordination between counter-ambush tactics, combat skills of soldiers on the battleground, such as the courageous action of the US and ARVN combatants, surging out of the camp, to assault the enemy with flamethrowers resulted in a heroic victory: in the evening of 10/25/1965 the relief task force linked with the camp defenders, ending the siege of Pleiku that the command of B3 Battle Front had planned since Spring 1965. “…The field commander can go to sleep to wait for the news of victory when the campaign starts!!” Marshall Montgomery of the British Royal Armored has so dictated to emphasize the determinant role of organization, general staff planning in a big campaign. Duc Co and Pleime had confirmed this determinant role of the preparation in planning, execution, organization, general staff (it is without saying, the realities of the battlefield and the combat skills of the soldiers on the battleground constitute the other important factors). The victory of Pleime had been glorified by General Vinh Loc who made it into the combat and victory symbol of II Corps. II Corps HQ was named Pleime City. But it seemed that not many people (in and outside the army) knew that Colonel Chief of Staff Nguyen Van Hieu practically stayed up all nights and days during the 20th, …the 25th in the command post bunker of Camp Duc Co, to make use of the stronger radio signal network of US Special Force units which allowed easy communication and coordination with American commanders of various branches and units, Air Force, Special Force, Infantry, Air Cavalry during the entire operation.

Applying the principles from military textbooks, II Corps General Staff collaborated closely with US 1st Air Cavalry. Furthermore, an excellent friendship blossomed between two individuals, Colonel Nguyen Van Hieu and Commander Kinnard of US 1st Air Cavalry through the two victories of Duc Co and Pleime. The two sides planned together with a pursuit operation going after the fleeing units of 32nd, 33rd and 66th Regiments NVA to prevent them the chance to catch their breath, as they had always enjoyed in the past since they always held the upper hand on the battlefield. With the quasi unlimited capabilities of helicopters (US 1st Air Cavalry with more 600 helicopters was the first and unique unit that had the biggest tactical mobile capability as compared to all units operating in the entire world), US 1st Air Cavalry dispatched 1st Battalion and 2nd Battalion of 7th Regiment/1st Air Cavalry Division in coordination with four ARVN Airborne Battalions into the battleground at Ia Drang Valley, close to the Kampuchean border, the stronghold of Battle Front B3. The ARVN Airborne Battalions were commanded by Airborne Chief of Staff, LTC Ngo Quang Truong with the assistance of a US advisor going by the name of Major Norman Schwarzkopf. With a operational plan well designed, cautious, anticipating all eventualities, and with seasoned paratroopers under the command of competent officers, combined with air cavalry mobility, modern technology, awesome firepower and full support from US1st Cavalry Division helicopters, the enemy pursuit operation at the tip of Ia Drang River, close to the Kampuchean border in 11/1965, was one of rarest successful joint operations of ARVN and US Army in the entire war since 1960.

1966. Binh Dinh; 1970. Snoul

But General Nguyen Van Hieu was not only competent in strategy; he was also a resourceful commander on the battlefield. The following battles will attest to his competency.

Binh Dinh was one of the largest provinces in the Center, as well in entire South Vietnam, with twenty-two districts, and the highest density in terms of population (almost one million), but it was also the province which counted the largest communist sympathizers and collaborators. During the 1945-1954 war, it was the capital of Region 5 VC. The French Expeditionary Army was not able to set foot in this region. It only fell into governmental control after 7/20/1965. In this area, the Communists had the NVA 3 Yellow Stars Division, a Governor and Command Post composed of numerous local battalions, and innumerable guerillas. This network, strengthened through a decade of war in the 50s, had been set in place before the Communists left in 1954. Based on the “search and destroy” adopted by General Westmoreland and the ARVN Joint of General Staff, the province was divided into three regions: the southern region (next to Tuy Hoa/Phu Yen border) comprising the outskirt of Qui Nhon City, Phu Phong, Tuy Phuoc, and Van Canh Districts was put under the control of Korean Tiger Division; the mountaineous western region (next to Pleiku/Kontum border) comprising An Khe, Vinh Thanh, An Lao and Hoai An Districts was put under the control of US 1st Cavalry Division, with An Lao sanctuary (stretching along An Lao river, the northern branch of Lai Giang River which poured into the sea at Bong Son/Hoai Nhon, the richest delta area of the Center), and constituted an important rear base of the entire Region 5 NVA; the northern and eastern region (stretching along the coastal area, next to Quang Ngai border), the most populous area comprising Hoai An (Bong Son), Tam Quan, Phu My, Phu Cat Districts was put under the control of ARVN 22nd Infantry Division, under the command of General Nguyen Van Hieu. He was outstanding as a commander in this Region II; and yet he was only a colonel although he was the person who had designed all those victories in 1965 above-mentioned. He held the rank of colonel since 11/1963.

General Hieu took over the command of 22nd Infantry Division in June 1966, and by the end of the year (November), the newly appointed Commander scored a battle victory at Phu Cu Pass (Phu My District). At that time, we, the attached unit (3rd Airborne Task Force-Pnn) established a blockage position on the mountainside, and witnessed our friendly unit (42nd Regiment/22nd Division) joining forces with the armored squadron of M113s in sweeping the enemy from National Route 1 into the mountains. The battle unfolded just like a military WWII documentary film. Infantrymen in front line formation followed M113 armored vehicles launched fierce assaults, after a salvo of artillery firing, just like Middle Age’s knights charging in combat. Airborne Task Force Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Khoa Nam observed the battle from the mountainside with binocular. Although he was a man parsimonious in words, he had to utter his admiration: “Colonel Hieu conducts his troops like a seasoned “armor officer”, and combatants of 22nd Division fought as elegantly as our paratroopers.” Those were sincere words from a combatant complimenting another combatant on the battlefield. Not allowing the enemy to recuperate (after the victories of Pleime and Duc Co), now with full authority of a division commander, Colonel Hieu gave order to pursue the enemy to destroy units of 3rd Yellow Star Division NVA, to prove who was the master on this battlefield in Region 5 VC, named “Nam Eo”, a code name the enemy uttered with pride, an impenetrable area that the government of the 1st Republic of Vietnam of President Ngo Dinh Diem had to spend two years (1955-1957) to pacify.

The American-Vietnamese-Korean joint operation started on D-Day with US1st Cavalry Division entering the areas of Hoai An and Vinh Thanh Districts. US Airborne troops discovered numerous treasures, military equipment hidden in secure secret areas (rear bases of Region 5/3rd Division NVA). However, the enemy regular units avoided all contacts, because they realized the overwhelming firepower of the US Air Cavalry. Therefore, at 11:00 pm on D+3 , US 1st Cavalry Division Commanding General came to see General Hieu (promoted to Brigadier General in 11/1966) at 22nd Infantry Division headquarters with a request that 22nd Infantry Division abandoned the plan to attack west of Phu My as previously set, in order to join with 1st Air Cavalry to invade An Lao where he believed 3rd Division NVA was concentrating. Commanding General Kinnard rationalized: “Today, I had a company of Rangers heli-lifted into that area to search and destroy the enemy, but no contact was made. I knew I did wrong in so doing because I stepped in the operational area of the 22nd Division, but due to my eagerness to destroy the enemy, I was forced to do so”. General Hieu had Major Trinh Tieu, his G2 intelligence officer defend his position: “Major General, the Communists were extremely careful in avoiding making contact with the American units because they were afraid of your firepower. I am convinced the 22nd Division will make contact with the 3 Yellow Stars Division at this target.” He added: “I had encountered a Viet Cong guerilla who resided in the mountainous areas west of Phu My district. I had spent a lot of money to feed this guerilla's family. A few days ago, he informed me that numerous units of the 3 Yellow Stars Division rallied at the boundary areas between Phu My and Hoai An districts.” And so General Hieu concluded to General Kinnard: "According to the plan discussed by the three Vietnamese, American, Korean Divisions, our Division will go into our operational area tomorrow, we should not hasten to change our plan too early."

Based on intelligence information provided by G2, General Hieu ordered Lieutenant Colonel Bui Trach Dzan, Commander of 41st Regiment to only use 2 Infantry Battalions and the Regiment Command Post unit to enter the operational area early in the morning and when the units reached the designated area around 3:00 p.m., have the units settled down, have the soldiers take their supper and dig extremely solid defensive fox holes. This area was infested with Viet Cong informants. Knowing perfectly that these informants would signal to the Communists to attack our units when they knew the number of our committed units in the operational area, General Hieu made a plan to counter-attack them with the force of armored cavalry. General Hieu hid one Infantry Battalion and one Armored Cavalry Squadron at a distance of 10 km away from the operational area, out of enemy sight. At 2:00 a.m., Lieutenant Colonel Bui Trach Dzan radioed back to the headquarters that the enemy began attacking his units. General Hieu gave the order to the Armored Cavalry Squadron and the reserved Battalion to speed into the targeted area and to go behind the enemy line, to encircle the enemy, preventing the enemy from withdrawing and to destroy the enemy. The American 1st Cavalry, finding out that we came into contact with the enemy, sent up helicopters to provide lightning support. Artillery of both Vietnamese and American Divisions fired continuously in support. Luminous rockets launched by the American 1st Cavalry were so bright that night became as clear as day. The Communists' night attack planning was sapped. Thirty minutes later, the Armored Cavalry Squadron and the reserved Battalion arrived at the scene on time, encircled the enemy and killed a lot of them. At 5:00 a.m. the Communists had to leak their wounds, dispersed and withdrew into the jungle, leaving behind 300 KIA lying all over the place, numerous weapons and ammunition scattered all over the operational area. Military experts estimate that for one dead left on the battlefield, the unit should have suffered three times more in a human loss. Operation Eagle Claw 800 and other operations at battalion level of this division since General Nguyen Van Hieu held its command (6/1966) had in six months transformed 22nd Division from an average unit to become:

This evaluation pointed out other merits. We conclude with the following thought: If all ARVN Infantry Divisions had as commanders like Generals: Nguyen Viet Thanh, Truong Quang An, Ngo Quang Truong, Nguyen Khoa Nam, Tran Van Hai, Nguyen Van Hieu, a decade sooner; and heroes like Nguyen Viet Can, Le Nguyen Vy, Le Van Hung, Ho Ngoc Can, Nguyen Huu Thong, Dang Phuong Thanh, Nguyen Xuan Phuc, LTC Nguyen Van Long of the Police Force… were promoted sooner to the rank of general and given the task of defending the country, then perhaps the dark day of April 30, 1975, would not have happened. Indeed, this suffering was not a lot of just one individual alone.

General Nguyen Van Hieu’s military leadership skills did not stop at division level with infantry units, but it reached up to the corps level with coordination of different army branches. Operation Toan Thang 46 attacked the R Central Committee located in the Fish Hook area, northwest Loc Ninh, on the other side of Vietnam-Kampuchea. Fish Hook area was the headquarters of the 5th Division VC. This unit allegedly belonged to the South Vietnam Liberation Armed Force, but the majority of its cadres were Northerner with its Political Commissary a pure native of Hanoi, from the lowest level. This structure was implemented entirely since Ba Cap (name unknown, who replaced Chin Chien, a Southerner) received the order from Le Duan to directly run the People Democratic Alliance For Peace since the beginning of 1970 (Truong Nhu Tang, Journal of a Vietcong, Johnathan Cape, London, England 1986, p197) in which The South Vietnam Liberation Front and its armed forces were subordinate elements. This area was also the rear base of 70th and 80th Groups which not only supported 5th Division NVA, but also the entire Fish Hook area, comprising Binh Long battleground inside Vietnam.

The operation involved 9th Regiment/5th Infantry Division, comprising 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Battalions, and 5th Recon Company. The Regiment was enforced by US 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment. The operation unfolded in five phases: phase 1, attack; phase 2, 3 and 4, search and destroy the enemy; phase 5, withdrawal back to Vietnam. This operation lasted only from May to July 1970 and its purpose was to test the enemy, to improve and coordinate the general staff network in preparation for more important subsequent operations, also inside Kampuchea aiming at 86th Rear Base, around Snoul city area. On October 14, 1970, III Corps Command gave order to 5th Division to launch operation Toan Thang 8/B/5 with the following forces: 1/ 1st Task Force, comprising 1st Armored Cavalry Squadron as main force; 2/ 9th Task Force, comprising 9th Regiment/5th Division, as secondary force; 3/ 333rd Task Force, comprising 18th Armored Cavalry Squadron and four Rangers battalions. The 5th Division Forward Command Post, established at Loc Ninh, conducted directly the operation and only reverted to Lai Khe when all involved combat units withdrew out of Kampuchea and returned safely to their base camps on November 1, 1970. Through these two (short-term and recon in force) operations, III Corps and 5th Division Commands were able to established two fundamental facts: 1/ In the phases when ARVN forces advanced, the enemy retreated deep into Kampuchean territories; 2/ When ARVN troops withdrew was when the battlefield became risky because the enemy then set up ambushes to harass the withdrawing troops. Consequently, despite the fact, numerous treasures, equipment, weapons and ammunition, foods were destroyed by the above-mentioned two operations, ARVN forces were still unable to dismantle the two main enemy forces, namely 174th and 275th Regiments NVA, and the 5th Division NVA central command and its subsidiary units in the region. Once more, Colonel Hieu proposed to General Tri to change operational concept: instead of search and destroy, we have to lure the enemy into a trap, then zero in to destroy them. Actually, in the operational area of the 5th Division, there was the 5th Division NVA with its two Regiments, the 174th and 275th. We use one regiment to lure the enemy; if the enemy attacks with a regiment, we will concentrate one division to counter-attack; if the enemy attacks with its entire division, we will throw in our three divisions (18th, 25th, and 5th) to counter-attack. General Tri approved this bold luring plan “Trick the Tiger down the Mountain” and he started the meticulous preparation plan through the remaining months of 1970. He had 11 positions of sensor devices set up around Snoul, and signal monitoring center established in Loc Ninh manned by personnel of G2 Intelligence Bureau round the clock.

On January 4, 1971, the luring plan commenced with the 9th Task Force comprising 9th Regiment/5th Division, 74th Ranger Battalion, 1st Armored Cavalry Squadron, and 5th Engineer Company, entering the operational area. But remaining clever as always, the enemy avoided all contacts; only two months later did the enemy show signs he is heading toward the trap. But an unexpected event occurred: on February 26, the helicopter carrying General Tri exploded. The Field Commander died at a critical phase of the campaign. On March 8, 1971, the enemy started shelling 9th Task Force positions, one-kilometer southwest Snoul. In the same period, the Battle of Low Laos, Lam Son 719, was getting bog down. General Nguyen Van Minh replaced General Tri as Corps Commander and approved the continuation of General Hieu’s luring plan, but not wholeheartedly, partly because it was not his own, partly because he was not capable of pursuing a plan that would eventually branch out to more complex and unanticipated avenues (It would require the use of the two divisions 18th and 25th in case the enemy concentrate a force the size of a division). All through the three months, both sides were monitoring the battlefield in preparation for a decisive attack. General Hieu ordered the 8th Regiment/5th Division to replace the 9th Regiment, a force taking up the name of 8th Task Force, comprising attached units to Rangers and Armored units remaining unchanged. With 5,000 troops, supported by US Air Force, General Hieu spanned out the operational area to push the enemy into the trap. On May 26, 1971, the enemy attacked Snoul but was rebuffed by the defender troops. On May 27, the enemy switched the attack directly to the west; and on May 29 gave assault at the command center of 8th Task Force with a force the size of a regiment and destroyed a communication network and the control station. General Hieu asked General Minh to send in III Corps reserved force to use a superior number to squash the enemy as planned. The American Advisors advised General Minh not to act on General Hieu’s request, but rather “to wait until the enemy concentrates much more and then to use B52 to annihilate them.” General Nguyen Van Hieu refused to accept these tactics because B52 would kill indiscriminately both foes and friends. He only asked B52 to bomb along the withdrawal route (Nationale Route 13 from Snoul to Loc Ninh), and the initial plan (use rescue force to counter-attack) that an order should be issued to 8th Task Force to retreat from Snoul. On May 30, 1971, as soon as General Minh washed his hands with an irresponsible statement: “Do as you wish!”, General Hieu boarded his helicopter to fly straight to Snoul where 8th Task Force CP was under direct enemy fire, to give in person the order of withdrawal to all leaders of units involved, after knowing that his request for B52 to support the withdrawal had been rejected by III Corps Command and by the American Advisors.

Nevertheless, the retreat from Snoul was a success (although 1/3rd of troops loss, and the 8th Regiment Deputy Commander was KIA), because units maintained their formation while withdrawing, and maintained their combat resolve after heavy losses, because commanders and troops were aware that their Division Commander remained close to them during the most dangerous time. The withdrawal also succeeded because it was supported by III Corps Assault Task Force of Brigadier General Tran Quang Khoi which attacked from Loc Ninh along National Route 13 toward Snoul. Finally, General Nguyen Van Hieu, after the event was dragged to justify himself for the loss in the battle of Snoul by appearing in front of Congress.

Withdrawal operation is the most difficult military exercise because it bears the defeat seed in itself. Military history, western and eastern, ancient and modern, have confirmed this fact through defeats of famous generals and invincible armies. Napoleon withdrew from Russia (1812); Mongolian armies withdrew from Dai Viet (13th Century). And not far off, on the Indochinese battle scene with the dismantling of Charton-Le Page army on Route 4 (1953); 100th Mobile Group (GM 100) on National Route 19 (1954). And recently, in the Battle of Low Laos, Lam Son 719 (February 1971): one Armored Cavalry Squadron, one Ranger Group, one of the best Infantry Divisions in the Army, two general reserved forces (1st Infantry Division, Airborne Division, Marine Corps Division) were used as guinea pigs by “third and fourth classes strategists”, those incompetent and worthless general officers. One should mention those so-called “National Ruling Committee Chairman, Military Committee Chairman, National Executive Committee Chairman, National Security Committee Chairman, Defense Minister, Chief of Joint General Staff.” They built their “glory” on our Soldier’s blood and bones, on many Soldiers’.

South Vietnam had begun to be lost since the so-called “tactical retreat” that started on Mars 15, in the Highlands.

III. A Murky Affair

What was the Military Pension Funds? How was it operated?

On July 4, 1972, in the uplifting atmosphere of the entire South Vietnam Military-Civilians defending the country on the battleground, the National Television Station in Saigon fired an augural explosion of a battlefront devoided of bullets but no less fierce: Major General Nguyen Van Hieu, Special Assistant to the Vice President in Charge of Anti-corruption, Special Investigation Committee Secretary-General of the Military Pension Funds (MPF) delivered his report after three months of work. The entire South Vietnamese people were filled with hope: both outside and inside enemies were attacked simultaneously. The nation’s fate was passing from a phase of tribulations and sufferings to the phase of glory and easiness. Major General Nguyen Van Hieu was indeed lighting up a candle of hope to entire South Vietnam. But unfortunately, only two years later, the Person who put up the light and the country were both terminated. Let us look back at this Pain that has not subsided even with the past thirty years.

Starting January 1968, each rank and file from ARVN regular and regional forces had 100 dong deducted from his monthly paycheck. With about 1 million troops, that amount bulged up in no time to an immense sum that no commercial or industrial entities could emulate. And if this money is only put in savings accounts, with the interests generated given to each soldier when discharged from the army, its initial concept was a plan to be lauded. In such a case, there would be no possibility of corruption, and dishonesty in the management of such anaccount. Or if more clever, wiser had been taken, this huge capital had been invested in enterprises, commercial tradings with honesty and good intention, to earn benefit for the investors, the entire troops who were contributing with their sweat and blood in the defense of South Vietnam; then this concept would constitute a hallmark, a source of strong economy, of wealth, of talents which would contribute in strengthening the Soldier and the Republic regime. Unfortunately, things did not occur according to everybody’s wishes. Let us go back to General Nguyen Van Hieu’s accusatory report, a task he had to deal with all alone in the long and unfortunate night of the country.

1.- Legal Shortcomings:

The Decree-Law #10 issued on August 6, 1950 (Under the Royal Regime of Emperor Bao Dai), Article 1- this ordinance explicitly forbids associations to have activities the purpose of which is to "divide up income." And yet the Board of Managers of the Military Pension Funds had used the capital of the Funds to purchase shares of two governmental companies: COGIVINA and SICOVINA; to establish the Industry and Commerce Bank, and four new companies: VICCO, VINAVATCO, ICICO, and FOPROCO with a capital of 1, 232, 753, 000. 00 VN dong (nearly 1,3 billion). Because they were not allowed to become members of the Fund to sign official certificated registered in the Saigon Notary Public Office, Lieutenant General Nguyen Van Vy (Defense Minister) and others registered in their private capacities. Then, knowing they were acting illegally in the establishment of certificates about the organization, the parties concerned signed “Transfer Shares Certificates” to the Association with the pledge: “These are Private Certificates” while the original certificates maintained in the Saigon Notary Public Office were still under the names of private individuals. The two legal shortcomings about the founding and organization of the association above-mentioned were caught by the Prime Minister’s Office which issued Memorandum # 2960 on August 27, 1970, requesting the Defense Ministry to rectify the organization according to current laws. However, Defense Minister Nguyen Van Vy and the Fund Board of Managers continued to operate the Fund based on its unlawful policy, in purchasing additional shares in the Vietnam Textile Company and in founding new companies: VN Industrial Construction Company (VICCO), VN Transportation Company (VINAVATCO), Industrial and Commercial Insurance Company (ICICO), Food Processing Company (FOPROCO).

In wrapping up this presentation regarding the organization and management of the Association, two facts needed to be mentioned: 1/ Defense Minister Nguyen Van Vy graduated from Hanoi Law School and French St. Cyr Military Academy; 2/ Soldiers started to contribute 100 dong/month in the Fund since January 1968, but not until May 9, 1969, did the Defense Ministry issued instructions and regulations determining the collection and managing of the money contributed by the entire Army. Due to dishonesty in organization and management as above-mentioned, the Fund obviously exhibits the following flaws: there are huge discrepancies between receipts and expenditures, which cannot be explained. This flaw is stemmed from the different accounting methods adopted in each unit. There are more than 400 units in the entire country (including the central accounting unit) which are not maintaining transparent bookkeeping (no dates, no signatures of the chief accountant, any pagination, etc.)

From these obstacles, the Investigation Committee could only work based on two concrete numbers: the amounts collected from 1968 to 1981; the amount the Fund actually disbursed to members who had been discharged, or to next of kins (of soldiers who had been killed in action or missing in action).

From a simple and sincere request, the Investigation Committee obtained two total amounts (up to December 31, 1971), but without a plausible explanation even with an open mind and generous understanding.

The actual total amount of receipts from 1968 to 1981: 3, 267, 631, 585. dong

The actual total amount of expenditures:

a/ From 1968 to 1969:: 14, 487, 642 dong

b/ From 1970 to 1971: 293, 287, 047 dong

In summary: In two years (1970-1971) the Fund paid to discharged soldiers and next of kin of deceased soldiers an amount twenty times the amount of the past two years (1968-1969)!!

2/ Cases of abuses, violations:

However, these legal violations could well be corrected and justified if those who managed the Fund would heed to the voice of conscience. This monetary contribution made by soldiers to the Fund is indeed the price of their blood and their families’. But it is has been used in enterprises that benefit an individual (and a group of individuals), in the following manner: The building located at 8 Nguyen Hue Street was constructed to be the Industrial Commercial Bank headquarters and offices of four newly found companies as above-mentioned. The decision to construct such a building did not come from the Board of Managers of the Fund but Defense Minister Nguyen Van Vy. He is only the Honorary Chairman who does not have the authority over the Board of Managers. This violation was not an unintentional management act and has led to serious consequences.

The Defense Ministry employed army personnel and resources (Engineer Corps/Defense Ministry) to construct a building for an Association (private). It was only one year later that the Investigation Committee approved and validated the decision of the Defense Minister. The Defense Minister signed Decision No. 1815-QP/TCTT/QD (on August 8, 1969), governing formation of three committees named respectively the Works Committee, the Procurement Committee, and the Control Committee. These three committees granted full authority to the Defense Minister in person in the management, decision in all matters: procurement of all the material needed for construction and installation, examination and approval of costs of procurement and installation services, approval of reports of receipt of the material and construction work, examination of records of payment, signing and issuing checks for payment to contractors, etc. Because the power limitation had been determined by these three committees, the defense minister (no matter how conscientious and honest he might be) had violated managerial and financial principles that the Board of Managers had clearly defined: the checks must have the signature of the Cashier, the Secretary-General, and the Chairman of the Board of Managers, the former Minister of Defense not being one of them. This violation in the managerial and financial principles translated into the following transaction.

A businesswoman won the bid for the purchase of four (4) elevators to equip the building with a total amount of 79,000,000 dong (56 million for equipment; 23 million for installation). She got the intervention from the Defense Ministry (Who was the Defense Minister?) allowing her to import Hitachi elevators at the parallel exchange rate of 275 piasters for one dollar, while the Economy Ministry advised to importing preferably Otis elevators (USA) at 118 dong/one dollar. Without spending a penny, without laying out one dollar capital, just acting as an intermediary (between the owner of the building and the importer of the elevators), she gobbled the entire profit of 17 million dong (without taking into account the commission paid to the importer). Then the transaction of thirteen air-conditioners (to equip the building) with a businesswoman (another one) squandered about 19 million dong to a woman who knew how to talk her way in and out!!

But it was not only the case about the building of the Industrial Commercial Bank on Nguyen Hue Street. The Board of Managers of the Fund and even its Honorary Chairman, Defense Minister Nguyen Van Vy, continuously violated legal points in other cases:

Purchase of merchandise (2,069 aluminum doors) without a proper certificate from Trinh Phuong Binh (through the transaction of VICCO) with the price of 17 million dong, plus middleman's commission of two soldiers which amounted to 8 million 250 thousand; Binh received 2 million 290 thousand commission. The result was that these aluminum doors were discarded in a waste pile because they were not usable. All these had a cause: Binh is the husband of Nguyen Thi Chieu, the Defense Minister’s sister.

VICCO Company of General Le Van Kim (a close friend of the Defense Minister) purchased 650 tons of steel from Hung Nam Company with the price of 9 million dong, then left them unused; instead of purchasing the steel directly from Lucia Company to avoid paying 3 millions in commission to Hung Nam, because the Director of Hung Nam is Le Thi Thuong, General Kim’s sister.

We might forego these rather insignificant matters (although the loss amounted to tens and hundreds ofmillions) in considering these as only regular bidding transactions (although with the intention of favoring relatives of the Board of Mangement personnel), but we cannot let go violations against management principle that members of the Board of Managers have raised the degree of abuse to become a policy, a way of action as following:

A special detachment of personnel: a total number of soldiers (350 individuals) have been specially assigned to work at the Industrial Commercial Bank and six other companies managed by the army (as above-mentioned). This action could be tolerated if it did not violate the following points: a/ the Military Code never allows soldiers to be attached to a private position (even a soldier belonging to Regional Force); b/ a number of attached soldiers received paychecks from the private companies but never reported to the place of work; c/ the attached soldiers still received paychecks from the Defense Ministry’s budget. In summary, the Industrial Commercial Bank and the six companies are the places for draft dodgers being paid with the highest salaries.

But the greatest violation and abuse lies in the management of the fund. Just in the year of 1971, the Industrial Commercial Bank had the following expenditures: a/ personnel’s salaries: 38 million 119 thousand dong; b/ exterior transaction expenses: 19 million 431 thousand dong; c/ general purchasing expenses: 25 million 744 thousand dong. Total: 83, 285,000 dong. Besides this total, there was the sum paid to the Board of Managers: 16, 149, 398.00 dong. Not finished yet, just with Ma Hi, Director of Commission Division, who had the authority as a guarantor of the loaner, and for this service, he received a commission of 15% if the loan amount (without collateral). Just in one year, Director Ma Hi received from 15 to 30 million dong official commission (not counting his salary and other benefits). Meanwhile, the Military Pension Fund put in the savings account 249,300.000 dong at the Industrial Commercial Bank, which is 99.72% of the capital, for which the Fund only received a very small amount of interest. In summary, one million soldiers contribute their blood money to benefit a small group of individuals comprising the Board of Managers and the personnel system it has established.