- Sinh tháng 5 năm 1930 tại Hải Dương

- Nhập ngũ ngày 14-11-1953

- Xuất thân trường sĩ quan Thủ Đức Khóa 4

- Tiểu Đoàn Trưởng Tiểu Đoàn 2/Trung Đoàn 3/Sư Đoàn 1 năm 1963

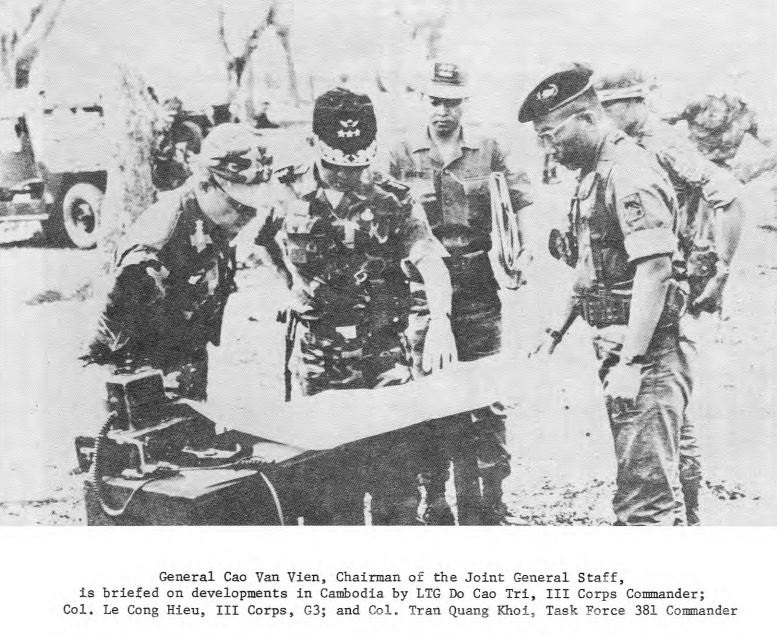

- Trưởng Phòng 3 Quân Đoàn III

Tướng Colin Powell viết về Đại Úy Võ Công Hiệu, Tiểu Đoàn Trưởng Tiểu Đoàn 2/Trung Đoàn 3/Sư Đoàn 1, khi ông được chỉ định làm cố vấn cho tiểu đoàn này. Vào lúc đó, Tiểu Đoàn 2 đóng quân tại một trại trong vùng A Shau:

“Captain Vo Cong Hieu, commanding 2d Battalion,” he said in passable English. Hieu was my ARVN counterpart, the man I would be advising. He was short, in his early thirties, with a broad face and an engaging smile. But for the uniform, I would have taken him for a genial schoolteacher, not a professional soldier.

(…)

Directly behind A Shau, a mountain loomed over us. I pointed toward it, and Hieu said with a grin, “Laos”. From that mountainside, the enemy could almost roll rocks down onto us. I wondered why the base had been established in such a vulnerable spot.

“Very important outpost.” Hieu assured me.

“But why is it here?”

“Outpost is here to protect airfield.” He said, pointing in the direction of our departing Marine helo.

“What’s the airfield here for?” I asked.

“Airfield here to resupply outpost.”

I would spend nearly 20 years, one way or another, grappling with our experience in this country. And over all that time, Vietnam rarely made much more sense than Captain Hieu’s circular reasoning on that January day in 1963. We’re here because we’re here, because we’re …”

(My American Journey, p. 82)

During his first tour of duty -- he completed two tours -- he befriended his Vietnamese counterpart, Capt. Vo Cong Hieu, who was in charge of the 400 Vietnamese soldiers that the young American captain was assigned to. During nights deep within the triple-canopy jungle of the A Shau Valley along the Laotian border, Captain Hieu and Captain Powell would trade stories: one telling of his traditions in Vietnam, the other telling of fast food and other American institutions.

Captain Hieu was reassigned after seven months, not to be heard of again by General Powell until 1991 when he called from Bangkok saying he and his family needed help to get to the United States. Captain Hieu, 72, who survived 12 years in a Vietnamese re-education camp, now lives in Minneapolis, and every now and again the two men from different cultures meet as citizens of the same country.

From an apartment decorated with photographs of the two -- taken when General Powell visited Minneapolis on speaking engagements -- Captain Hieu described the early relationship where each man depended on the other for his survival.

''We were in an area near Laos where the mountains were very high and the enemy was so close he could even throw stones at us,'' Captain Hieu said in a talk on the telephone. ''We were there to prevent their infiltration and resupply.''

The two got along well, he said, because Captain Powell ''convinced me that he was not an adviser who knew it all.'' The young Powell had virtually no Vietnamese language skills, Captain Hieu said, but even so they managed to bond against the terrors of leeches, the dangers of bamboo spikes poisoned with buffalo dung and the seeming futility of ever engaging the guerrillas.

When the last Americans evacuated Saigon in 1975, Mr. Hieu, who had since been promoted to colonel, was working in a sensitive intelligence position at the Presidential Palace. He was quickly picked up by the Vietcong as a prime candidate for re-education and dispatched to a series of hard work camps.

After his release in 1988, he sought help to leave Vietnam and managed to get to Bangkok and then the United States, where he lives as a retiree in Minneapolis with his wife. A daughter and son-in-law live nearby. He now suffers from polio, he said, a childhood disease that has worsened with age.

Secretary Powell, during a visit to Minneapolis in 1991 while he was still chairman of the Joint Chiefs, met Captain Hieu in a teary reunion and introduced him, to big applause, to an audience of local dignitaries. They keep in touch, with visits now and then. Most recently the secretary of state sent a postcard soon after assuming his new office, sending regards to a mutual friend from the war who remained behind in Ho Chi Minh City.

(Jane Perlez, New York Times, July 25, 2001)