(Before, During, and After the Americanization and Vietnamization)

The answer to this question from the American perspective would be obviously, "No, they were not, because we had to send in our troops in the first place; then, when we were in country, we did all the fighting and were winning the war; and then, not too long after we had left Ė two years to be precise - South Vietnam collapsed."

General Norman Schwarzkopf, who was a Captain and an American Advisor in 1964, wrote in It Doesn't Take A Hero that American officers began saying things like, "Theses guys can't handle the war. None of them are fighters. None of them are worth a damn."

The purpose of this paper is to show that this simplistic view stems from a misinformation of the real facts. I will not mention well-known and widely publicized military operations conducted by the ARVNs, such as the 1968 Tet Mau Than counter-offensives or the 1972 Easter counter-offensives at Kontum, Quang Tri and An Loc, and will only focuse on some sizeable and yet unheard of ones, before, during, after the Americanization and Vietnamization: Operation Quyet Thang 202 (April 1964), Operation Than Phong (August 1965), Operation Dan Thang 8 (October 1965), Operation Dai Bang 800 (February 1967), Operation Toan Thang 02 (May 1971) and Operation Svay Rieng (April 1974).

As a reference, let's note that the Americanization occurred in November 1965; the Vietnamization was implemented in November 1969; and the last American combat units departed in March 1973.

Unheard of ARVNsí Military Operations

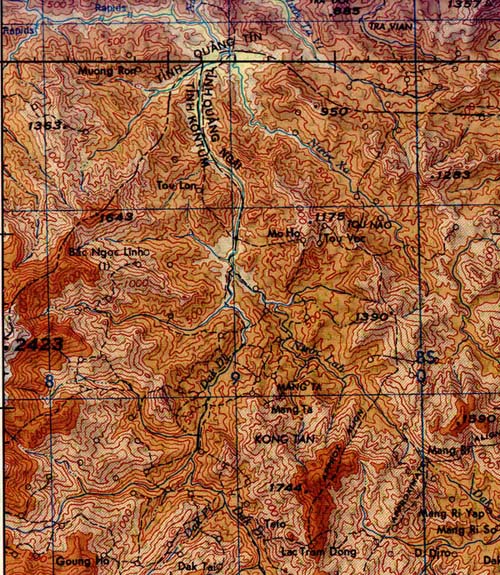

II Corps Command launched Operation Quyet Thang 202 aiming directly at the

impenetrable VC stronghold at Do Xa, embedded deeply in the Annamite Mountains, at the junction of three provinces of Kontum, Quang Ngai and Quang Tin, from April 27 to May 27 of 1964.

impenetrable VC stronghold at Do Xa, embedded deeply in the Annamite Mountains, at the junction of three provinces of Kontum, Quang Ngai and Quang Tin, from April 27 to May 27 of 1964.

Participating in the operation were units of 50th Regiment of 25th Division, four Ranger battalions and 1st Airborne Battalion.

Troops were ferried to two landing zones by three helicopters squadrons: USMC HMM-364 Squadron, 117th and 119th squadrons of US Army 52nd Aviation Battalion.

The VC attacked fiercely the helicopters at the landing zones during the two first days, and then vanished into the mountains, avoiding contacts with the invading troops. Operation Do Xa achieved the following results: a communication network of the Viet Cong command composed of five stations was destroyed, one of which was used to communicate with North Viet Nam, and the other four to link with provincial Viet Cong units; the enemy lost 62 killed, 17 captured, two 52 caliber machine guns, one 30 caliber machine gun, 69 individual weapons, and a large quantity of mines and grenades, engineer equipment, explosives, medicine, and documents; in addition, 185 structures, 17 tons of food and 292 acres of crops were destroyed.

In 1965, the Communists attacked all over the Highlands belonging to II Military Region. Early July 1965, three NVA regiments (32nd, 33rd and 66th) isolated completely the Highlands. ARVN units could not use National Route 1, 11, 14, 19 and 21, and all re-supplies to the Highlands had to be performed by air.

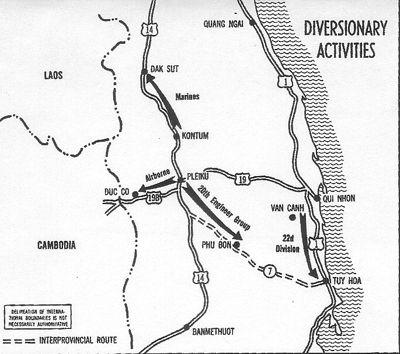

On July 8, 1965, II Corps Command launched Operation Than Phong to reopen National Route 19.

Contrary to the general practice of a road-clearing operation which consists in concentrating necessary troops to destroy in gradual steps the ambushes set up by the enemy along the highway, the design of the operation intended to interdict the enemy to

set up ambushed locations in resorting to diversionary tactic. From D-6 to D+2, the 22nd Division and the 3rd Armored Squadron attacked from Qui Nhon down to Tuy Hoa along National Route 1; the 2nd Airborne Task Force together with Regional Forces and Civilian Irregulars Defense Group Forces assaulted to retake Le Thanh District; the VNMC Alpha Task Force and the 42nd Regiment attacked from Pleiku up north to Dak Sut on National Route 14; and the 20th Engineer Group attacked from Phu Bon to Tuy Hoa to repair Inter-provincial Route 7.

set up ambushed locations in resorting to diversionary tactic. From D-6 to D+2, the 22nd Division and the 3rd Armored Squadron attacked from Qui Nhon down to Tuy Hoa along National Route 1; the 2nd Airborne Task Force together with Regional Forces and Civilian Irregulars Defense Group Forces assaulted to retake Le Thanh District; the VNMC Alpha Task Force and the 42nd Regiment attacked from Pleiku up north to Dak Sut on National Route 14; and the 20th Engineer Group attacked from Phu Bon to Tuy Hoa to repair Inter-provincial Route 7.

After sowing confusion among the enemy troops with the above-mentioned simultaneous big operations, the second phase of Operation Than Phong pressed ďthe Viet Cong from three directions with movements launched from Pleiku and Qui Nhon and a vertical envelopment from north of An Khe. These maneuvers were executed by a task force of the Pleiku sector departing from Pleiku, two task forces of the 22d Infantry Division departing from Qui Nhon, and a task force of two airborne battalions heli-borne into northern An Khe and attacking south with Task Force Alpha of the marines brigade conducting the linkup," and positioned "strong reserves composed of three battalions (one ranger, one marine, and one airborne) and two armored troops at tactical points: Pleiku, Soui Doi, An Khe, and Mang Pass." All these actions resulted in the free flow of cargo convoys during 5 days from D+3 to D+7, "allowing an initial buildup of 5,365 tons of supplies in Pleiku." Afterwards, operational units withdrew to their camps during D+8 and D+9.

As a result of Operation Than Phong, "the convoys transfused new life into the Highlands. Along with an immediate drop of 25 to 30 percent in the price of food and commodities, the population regained their feelings of security, confidence, and hope. School-boys in Pleiku voluntarily helped the troops in unloading the cargoes, and people who had started to evacuate now returned to their homesteads."

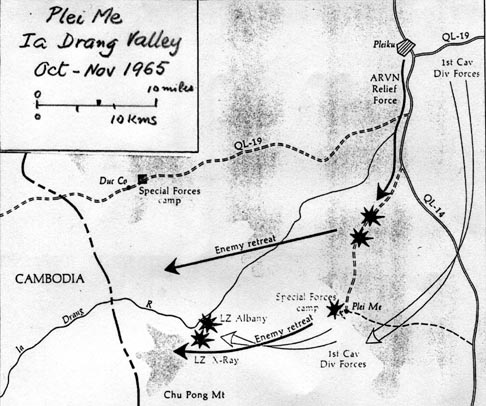

After the unsuccessful attempt to overcome the Special Force camp of Duc Co in August 1965, General Vo Nguyen Giap launched the Winter Spring Campaign aiming at slicing South

Vietnam into two pieces, from Pleiku in the Highlands to Qui Nhon in the coastal regions. The plan of General Chu Huy Man, VC Field Commander was as following: 1.33th Regiment NVA feigns to attack camp Pleime to entice II Corps to dispatch relief column from Pleiku; 2. 32nd Regiment NVA sets an ambush to destroy the relief column (an easy target without artillery support nearby); 3. after destroying the relief column, 32nd Regiment NVA joins force with 33rd Regiment NVA in overcoming camp Pleime; 4. in the meantime, with the defense of Pleiku weakened by the troops sent out to rescue camp Pleime, 66th Regiment NVA initiates a preliminary attack against II Corps HQ, awaiting 32nd and 33rd Regiments NVA to overcome camp Pleime and to join forces to attack and occupy Pleiku.

Vietnam into two pieces, from Pleiku in the Highlands to Qui Nhon in the coastal regions. The plan of General Chu Huy Man, VC Field Commander was as following: 1.33th Regiment NVA feigns to attack camp Pleime to entice II Corps to dispatch relief column from Pleiku; 2. 32nd Regiment NVA sets an ambush to destroy the relief column (an easy target without artillery support nearby); 3. after destroying the relief column, 32nd Regiment NVA joins force with 33rd Regiment NVA in overcoming camp Pleime; 4. in the meantime, with the defense of Pleiku weakened by the troops sent out to rescue camp Pleime, 66th Regiment NVA initiates a preliminary attack against II Corps HQ, awaiting 32nd and 33rd Regiments NVA to overcome camp Pleime and to join forces to attack and occupy Pleiku.

In order to counter General Chu Huy Manís clever moves, II Corps Command consulted with US 1st Cavalry Division and came up with the following plan: 1. II Corps feigns biting the bait by reinforcing camp Pleime with a unit of US Delta Force and a unit of ARVN Airborne Rangers; 2. and dispatches a task force from Pleiku to rescue camp Pleime; 3. US 1st Cavalry Division lends a brigade to reinforce the defense of Pleiku; 4. and heli-lifts artillery batteries to several locations near the ambush site to support the relief column when under attacked.

This plan neutralized the 66th Regiment NVA which remained inactive in Chu Prong area, destroyed the 33rd Regiment NVA at the ambush site, and the 32nd Regiment NVA had to abandon the siege of camp Pleime and withdrew dejected into the surrounding jungles.

In February 1967, the 22nd Division Command launched Operation Dai Bang 800. For three days prior to Vietnamese operation, units of US 1st Cavalry Division were unsuccessful in discovering the enemy in their operational areas. Instead of searching for the enemy, Operation Dai Bang 800 resorted to luring the enemy, by dispatching a reduced regiment to set up an over-night camp in the region of Phu My, knowing for certain that enemy spies inserted among the indigenous farmers would report the status of the operational troops. Meanwhile, a motorized infantry battalion and an armored unit were positioned 10 kilometers away, out of enemies screen radar. Thinking they had an easy target, the enemy attacked the camp with a regiment belonging to 3rd Division NVA at 2:00 am. Alerted by the regimentís commander, the reserved forces were sent in to cut the retreat route of the enemy and to join force with the defenders in an anvil-hammer tactic to destroy them. After a three-hour fierce battle, the enemy broke up contact with more than 300 deads and numerous weapons scattered all over the battleground.

The initial plan of Operation Toan Thang 02 was to lure the evasive enemy forces into a trap at Snoul in Kampuchea using 8th Task Force as bait. Unfortunately, General

Tri died unexpectedly in a helicopter accident in the end of February 1971, and General Minh, who replaced General Tri, did not want to follow through with the luring plan, when 8th Task Force was succeeding in attracting the enemy who gathered two Divisions (5th and 7th) around Snoul. The beleaguered troops of 8th Task Force, when neither rescue column nor B-52 bombers were in sight, were about to raise the white flag to surrender to the enemy.

Tri died unexpectedly in a helicopter accident in the end of February 1971, and General Minh, who replaced General Tri, did not want to follow through with the luring plan, when 8th Task Force was succeeding in attracting the enemy who gathered two Divisions (5th and 7th) around Snoul. The beleaguered troops of 8th Task Force, when neither rescue column nor B-52 bombers were in sight, were about to raise the white flag to surrender to the enemy.

The 5th Division Commander executed in time a withdrawal plan to bring back his troops to Loc Ninh. The troopís withdrawal was executed in three phases: (1) on 5/29/1971, 1/8th Battalion pierced through enemy blocking line at the northern outpost to rejoin the 8th Task Force Command Post located at Snoul market; (2) on 5/30/1971, 8th Task Force using 1/8th Battalion as the spear-head to pierce enemy blocking line, followed behind by 2/8th Battalion, Task Force Command Post, 1st Armored Squadron with 2/7th Battalion acting as rear cover, to withdraw from Snoul to the location defended by 3/8th Battalion, 3 kilometers Southeast of Snoul on National Route 13; (3) on 5/31/1971, 3/8th Battalion replaced 1/8th Battalion as the spear-head in piercing enemy blocking line, followed by 3/9th Battalion, 2/7th Battalion, Task Force Command Post, 1st Armored Squadron with 1/8th Battalion acting as rear cover, allowing 8th Task Force to reach the border on a 3 kilometer stretch and to return to Loc Ninh.

It is worthwhile mentioning that the soldiers of 1/8th Battalion that spearheaded the withdrawal conducted themselves samurai-like in that they followed to the tee their battalion commanderís instructions which ordered that they were not to lie down when the enemy opened direct gun fires or artillery fires and that their WIA and KIA comrades would be picked up by Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)

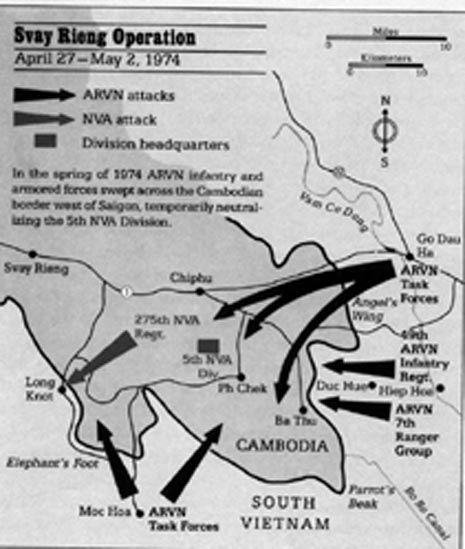

In 1974, III Corps Command applied Blitzkrieg (lightning war) tactic to alleviate the pressure exerted by 5th Division NVA originating from Svay Rieng Province in the

Parrotís Beak area inside Kampuchea territory aiming at base camp Duc Hue. Firstly, twenty mobile battalions were employed to surround the Parrotís Beak area. Secondly, on April 27, 49th Infantry Regiment and 7th Ranger Group were launched through the swamp lands around Duc Hue toward the Kampuchean border, and VNAF airplanes attacked positions of 5th Division NVA units. In the meantime, two Regional Force battalions belonging to IV Corps moved from Moc Hoa up north to establish blocking positions on the southwestern edge of the 5th Division NVAís logistical base and assembly area.

Parrotís Beak area inside Kampuchea territory aiming at base camp Duc Hue. Firstly, twenty mobile battalions were employed to surround the Parrotís Beak area. Secondly, on April 27, 49th Infantry Regiment and 7th Ranger Group were launched through the swamp lands around Duc Hue toward the Kampuchean border, and VNAF airplanes attacked positions of 5th Division NVA units. In the meantime, two Regional Force battalions belonging to IV Corps moved from Moc Hoa up north to establish blocking positions on the southwestern edge of the 5th Division NVAís logistical base and assembly area.

On April 28, eleven battalions were launched into the battleground to conduct preliminary operation in preparation of the main offensive.

In the morning of April 29, three armored squadrons of the III Corps Assault Task Force rushed across the Kampuchean border from west Go Dau Ha, aiming directly at 5th Division NVA HQ.

Meanwhile, a task force composing of infantry and armor of IV Corps, originating from Moc Hoa, maneuvered across the Kampuchean border into Elephantís Foot area to threaten the retreat of 275th Regiment NVA. The three armored squadrons continued their three-pronged advance 16 kilometers deep into the Kampuchean territory before they veered south toward Hau Nghia Province, and helicopters debarked troops unexpectedly on enemy positions, while other ARVN units conducted rapid operations into the region between Duc Hue and Go Dau Ha.

On May 10, when the last ARVN units returned to their base camp, enemy communications and supplies networks were seriously disrupted. The Communists suffered 1,200 deads, 65 prisoners, and tons of weapons captured; while, due to speed, secrecy and coordination factors of a multi-faced operation, the ARVN only suffered less than 100 casualties.

Historical Distortions

The American military literature tends to glorify American unitsí actions and to demonize ARVNsí actions. At times, it even ignores the existence of ARVNs all together. One such instance can be found in the case of Operation Dan Thang 8 which is better known by the Americans as Pleime Battle.

- A Study of American Involvement in the Vietnam War (1965-1969)

(http://macv.cjb.net)

The Ia Drang Valley (November, 1965)

This was a battle between the NVA 66th Regiment and the US 1st Cavalry Division. It started when NVA attacked a Special Forces camp at Plei Me. The 1st Cav was called in and drove off the NVA. The 1st Cav was ordered to sweep the Ia Drang Valley and to destroy the NVA there. The 1st Battalion of the 7th Cavalry landed at LZ X-Ray, but was immediately attacked by the NVA. The 1/7 was heavily outnumbered and had to call in heavy support. The fire support held off the NVA and the 1/7 was reinforced. The NVA assaulted the troopers several more times but failed and withdrew. The 2/7, was ambushed on its way to LZ Albany and took horrendous casualties, again fire support kept the US forces from being overrun. After that the battle was over.

- Ground Combat Operations - Vietnam 1965 Ė 1972

(https://www.angelfire.com/al2/vietnamops)

Silver Bayonet - 23 Oct-20 Nov 65 - 29 days - 5 Bns - 1st Cavalry Division - operation in Ia Drang Valley of Pleiku Province - VC/NVA KIA 1,771 - US KIA 240

- 1st US Cavalry's Website - Vietnam War

(http://www.first-team.us/journals/1stndx06.html)

On 10 October 1965, in Operation "Shiny Bayonet", the First Team initiated their first brigade-size airmobile action against the enemy. The air assault task force consisted of the 1st and 2nd Battalions 7th Cavalry, 1st Squadron 9th Cavalry, 1st Battalion 12th Cavalry and the 1st Battalion 21st Artillery. Rather than standing and fighting, the Viet Cong chose to disperse and slip away. Only light contact was achieved. The troopers had but a short wait before they faced a tougher test of their fighting skills; the 35-day Pleiku Campaign.

On 23 October 1965, the first real combat test came at the historic order of General Westmoreland to send the First Team into an air assault mission to pursue and fight the enemy across 2,500 square miles of jungle. Troopers of the 1st Brigade and 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry swooped down on the NVA 33rd regiment before it could get away from Plei Me. The enemy regiment was scattered in the confusion and was quickly smashed.

On 09 November, the 3rd Brigade joined the fighting. Five days later, on 14 November, the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, reinforced by elements of the 2nd Battalion, air assaulted into the Ia Drang Valley near the Chu Prong Massif. Landing Zone (LZ) X-Ray was "hot" from the start. At LZ X-Ray, the Division's first Medal of Honor in the Vietnam War was awarded to 2nd Lt. Walter J. Marm of the 1st Battalion 7th Cavalry. On 16 November, the remainder of the 2nd Battalion relieved the 1st Battalion at LZ X-Ray, who moved on to set up blocking positions at LZ Albany. The fighting, the most intensive combat in the history of the division, from bayonets, used in hand-to-hand combat, to artillery and tactical air support, including B-52 bombing attacks in the areas of the Chu Pong Mountains, dragged on for three days. With the help of reinforcements and overwhelming firepower, the 1st and 2nd Battalions forced the North Vietnamese to withdraw into Cambodia.

When the Pleiku Campaign ended on 25 November, troopers of the First Team had paid a heavy price for its success, having lost some 300 troopers killed in action, half of them in the disastrous ambush of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, at LZ Albany. The troopers destroyed two of three regiments of a North Vietnamese Division, earning the first Presidential Unit Citation given to a division in Vietnam. The enemy had been given their first major defeat and their carefully laid plans for conquest had been torn apart.

The 1st Cavalry Division returned to its original base of operations at An Khe on Highway 19.

- LZ X-Ray

(http://www.weweresoldiers.net/campaign.htm)

In late October '65, a large North Vietnamese force attacked the Plei Me Special Forces Camp. Troops of the 1st Brigade of the 1st Cavalry were sent into the battle. After the enemy was repulsed in early November, the 3rd Brigade replaced the 1st Brigade. After three days of patrolling without any contact, Hal Moore's 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry was ordered to air assault into the Ia Drang Valley on Nov 14, his mission: Find and kill the enemy!

At 10:48 AM, on November 14th, Moore was the first man out of the lead chopper to hit the landing zone, firing his M16 rifle. Little did Moore and his men suspect that FATE had sent them into the first major battle of the Vietnam War between the American Army and the People's Army of Vietnam - Regulars - and into history.

The ARVNs were no where to be seen!

Besides casting aside the ARVNs, these four web sites committed another historical distortion when they advanced Ia Drang Valley Battle as the main battle with Pleime Battle as its preliminary battle; while in reality, Pleime Battle was the main battle with Ia Drang Valley Battle its mopped up operation, along with Operation Duc Co, which all four web sites failed to mention all together.

The above mentioned operations show that the ARVNs fought

They were downright great!

Nguyen Van Tin

02.06.2005

(Paper presented at the Fifth Triennial Symposium organized by Vietnam Center, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, on March 18, 2005)