The New Opium Monopoly

Premier Ky's air force career began when he returned from instrument flying school in France with his certification as a transport pilot and a French wife. As the Americans began to push the French out of air force advisory positions in 1955, the French attempted to bolster their wavering influence by promoting officers with strong pro-French citizen, he was promoted to colonel "almost overnight" and became the first ethnic Vietnamese to command the Vietnamese air force. Lieutenant Ky's French wife was adequate proof of his loyalty, and despite his relative youth and inexperience, he was appointed commander of the First Transport Squadron. In 1956 Ky was also appointed commander of Saigon's Tan Son Nhut Air Base, and his squadron, which was based there, was doubled to a total of thirty-two C-47s and renamed the First Transport Group. While shuttling back and forth across the countryside in the lumbering C-47s may have lacked the dash and romance of fighter flying, it did have its advantages. Ky's responsibility for transporting government officials and generals provided him with useful political contacts, and with thirty-two planes at his command, Ky had the largest commercial air fleet in South Vietnam. Ky lost command of the Tan Son Nhut Air Base, allegedly, because of the criticism about the management (or mismanagement) of the base mess hall by his sister, Madame Nguyen Thi Ly. But he remained in control of the First Transport Group until the anti-Diem coup of November 1963. Then Ky engaged in some dextrous political intrigue and, despite his lack of credentials as a coup plotter, emerged as commander of the entire Vietnamese air force only six weeks after Diem's overthrow.

As air force commander, Air Vice-Marshal Ky became one of the most active of the "young Turks" who made Saigon political life so chaotic under General Khanh's brief and erratic leadership. While the air force did not have the power to initiate a coup singlehandedly, as an armored or infantry division did, its ability to strafe the roads leading into Saigon and block the movement of everybody else's coup divisions gave Ky a virtual veto power. After the air force crushed the abortive September 13, 1964 coup against General Khanh, Ky's political star began to rise. On June 19, 1965, the ten-man National Leadership Committee headed by Gen. Nguyen Van Thieu appointed Ky to the office of premier, the highest political office in South Vietnam.

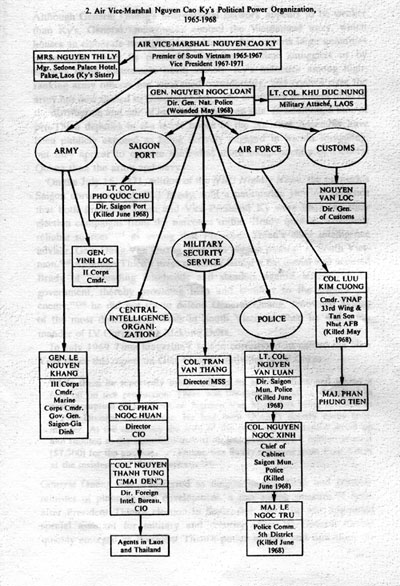

Although he was enormously popular with the air force, Ky had neither an independent political base nor any claim to leadership of a genuine mass movement when he took office. A relative newcomer to politics, Ky was hardly known outside elite circles. Also, Ky seemed to lack the money, the connections, and the capacity for intrigue necessary to build up an effective ruling faction and restore Saigon's security. But he solved these problems in the traditional Vietnamese manner by choosing a power broker, a "heavy" as Machiavellian and corrupt as Bay Vien or Ngo Dinh Nhu - Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan.

Loan was easily the brightest of the young air force officers. His career was marked by rapid advancement and assignment to such technically demanding jobs as commander of the Light Observation Group and assistant commander of the Tactical Operations Center. Loan also had served as deputy commander to Ky, an old classmate and friend, in the aftermath of the anti-Diem coup. Shortly after Ky took office he appointed Loan director of the Military Security Service (MSS). Since MSS was responsible for anticorruption investigation inside the military, Loan was in an excellent position to protect members of Ky's faction. Several months later Loan's power increased significantly when he was also appointed director of the Central Intelligence Organization (CIO), South Vietnam's CIA, without being asked to resign from the MSS. Finally, in April 1966, Premier Ky announced that General Loan had been appointed to an additional post - director general of the National Police. Only after Loan had consolidated his position and handpicked his successors did he "step down" as director of the MSS and CIO. Not even under Diem had one man controlled so many police and intelligence agencies.

In the appointment of Loan to all three posts, the interests of Ky and the Americans coincided. While Premier Ky was using Loan to build up a political machine, the U.S. mission was happy to see a strong man take command of "Saigon's police and intelligence communities" to drive the NLF out of the capital. Lt. Col. Lucien Conein says that Loan was given whole-hearted U.S. support because

We wanted effective security in Saigon above all else, and Loan could provide that security. Loan's activities were placed beyond reproach and the whole three-tiered US advisory structure at the district, province and national level was placed at his disposal.

The liberal naivete that had marked the Kennedy diplomats in the last few months of Diem's regime was decidedly absent. Gone were the qualms about "police state" tactics and daydreams that Saigon could be secure and politics "stabilized" without using funds available from the control of Saigon's lucrative rackets.

With the encouragement of Ky and the tacit support of the U.S. mission, Loan (whom the Americans called "Laughing Larry" because he frequently burst into a high-pitched giggle) revived the Binh Xuyen formula for using systematic corruption to combat urban guerrilla warfare. Rather than purging the police and intelligence bureaus, Loan forged an alliance with the specialists who had been running these agencies for the last ten to fifteen years. According to Lieutenant Colonel Conein, "the same professionals who organized corruption for Diem and Nhu were still in charge of police and intelligence. Loan simply passed the word among these guys and put the old system back together again."

Under Loan's direction, Saigon's security improved markedly. With the "door-to-door" surveillance network perfected by Dr. Tuyen back in action, police were soon swamped with information. A U.S. Embassy official, Charles Sweet, who was then engaged in urban pacification work, recalls that in 1965 the NLF was actually holding daytime rallies in the sixth, seventh, and eight districts of Cholon and terrorist incidents were running over forty a month in district 8 alone. Loan's methods were so effective, however, that from October 1966 until January 1968 there was not a single terrorist incident in district 8. In January 1968, correspondent Robert Shaplen reported that Loan "has done what is generally regarded as a good job of tracking down Communist terrorists in Saigon..."

Putting "the old system back together again," of course, means reviving large-scale corruption to finance the cash rewards paid to these part-time agents whenever they delivered information. Loan and the police intelligence professionals systematized the corruption, regulating how much each particular agency would collect, how much each officer would skim off for his personal use, and what percentage would be turned over to Ky's political machine. Excessive individual corruption was rooted out, and Saigon-Cholon's vice rackets, protection rackets, and payoffs were strictly controlled. After several years of watching Loan's system in action, Charles Sweet feels that there were four major sources of graft in South Vietnam: (1) sale of government jobs by generals or their wives, (2) administrative corruption (graft, kickbacks, bribes, etc), (3) military corruption (theft of goods and payroll frauds), and (4) the opium traffic. And out of the four, Sweet has concluded that the opium traffic was undeniably the most important source of illicit revenue.

As Premier Ky's power broker, Loan merely supervised all of the various forms of corruption at a general administrative level; he usually left the mundane problems of organization and management of individual rackets to the trusted assistants.

In early 1966 General Loan appointed a rather mysterious Saigon politician named Nguyen Thanh Tung (known as "Mai Den" or "Black Mai") director of the Foreign Intelligence Bureau of the Central Intelligence Organization. Mai Den is one of those perennial Vietnamese plotters who have changed sides so many times in the last twenty-five years that nobody really knows too much about them. It is generally believed that Mai Den began his checkered career as a Viet Minh intelligence agent in the late 1940s, became a French agent in Hanoi in the 1950s, and joined Dr. Tuyen's secret police after the French withdrawal. When the Diem government collapsed, he became a close politial adviser to the powerful I Corps commander, Gen. Nguyen Chanh Thi. However, when General Thi clashed with Premier Ky during the Buddhist crisis of 1966, Mai Den began supplying General Loan with information on Thi's movements and plans. After General Thi's downfall in April 1966, Loan rewarded Mai Den by appointing him to the Foreign Intelligence Bureau. Although nominally responsible for foreign espionage operations, allegedly Mai Den's real job was to reorganize opium and gold smuggling between Saigon and Laos.

Through his control over foreign intelligence and consular appointments, Mai Den would have had no difficulty in placing a sufficient number of contact men in Laos. However, the Vietnamese military attache in Vientiane, Lt. Col. Khu Duc Nung, and Premier Ky's sister in Pakse, Mrs. Nguyen Thi Ly (who managed the Sedone Palace Hotel), were Mai Den's probable contacts.

Once opium had been purchased, repacked for shipment, and delivered to a pickup point in Laos (usually Savannakhet or Pakse), a number of methods were used to smuggle it into South Vietnam. Although no longer as important as in the past, airdrops in the Central Highlands continued. In August 1966, for example, U.S. Green Berets on operations in the hills north of Pleiku were startled when their hill tribe allies presented them with a bundle of raw opium dropped by a passing aircraft whose pilot evidently mistook the tribal guerrillas for his contact men. Ky's man in the Central Highlands was II Corps commander Gen. Vinh Loc. He was posted there in 1965 and inherited all the benefits of such a post. His predecessor, a notoriously corrupt general, bragged to colleagues of making five thousand dollars for every ton of opium dropped into the Central Highlands.

While Central Highland airdrops declined in importance and overland narcotics smuggling from Cambodia had not yet developed, large quantities of raw opium were smuggled into Saigon on regular commercial air flights from Laos. The customs service at Tan Son Nhut was rampantly corrupt, and Customs Director Nguyen Van Loc was an important cog in the Loan fund-raising machinery. In a November 1967 report, George Roberts, then chief of the U.S. customs advisory team in Saigon, described the extent of corruption and smuggling in South Vietnam:

Despite four years of observation of a typically corruption ridden-agency of the GVN (Government of Vietnam), the Customs Service, I still could take very few persons into a regular court of law with the solid evidence I possess and stand much of a chance of convicting them on that evidence. The institution of corruption is so much a built in part of the government processes that it is shielded by its very pervasiveness. It is so much a part of things that one can't separate "honest" actions from "dishonest" ones. Just what is corruption in Vietnam? From my personal observations, it is the following:

The very high officials who condone, and engage in smuggling, not only of dutiable merchandise, but undercut the nation's economy by smuggling gold and worst of all, that unmitigated evil - opium and other narcotics; The police officials whose "check points" are synonymous with "shakedown points"; The high government official who advises his lower echelons of employees of the monthly "kick in" that he requires from each of them... The customs official who sells to the highest bidder the privilege of holding down for a specific time the position where the graft and loot possibilites are the greatest.

It appeared that Customs Director Loc devoted much of his energies to organizing the gold and opium traffic betwwen Vientiane, Laos, and Saigon. When 114 kilos of gold were intercepted at Tan Son Nhut Airport coming from Vientiane, George Roberts reported to U.S. customs in Washington that "There are unfortunate political overtones and implications of culpability on the part of highly placed personages." Director Loc also used his political connections to have his attractive niece hired as a stewardess on Royal Air Lao, which flew several times a week between Vientiane and Saigon, and used her as a courier for gold and opium shipments. When U.S. customs advisers at Tan Son Nhut ordered a search of her luggage in December 1967 as she stepped off a Royal Air Lao flight from Vientiane they discovered two hundred kilos of raw opium. In his monthly report to Washington, George Roberts concluded that Director Loc was "promoting the day-to-day system of payoffs in certain areas of Customs' activities."

After Roberts filed a number of hard-hitting reports with the U.S. mission, Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker called him and members of the customs adviory team to the Embassy to discuss Vietnamese "involvement in gold and narcotics smuggling." The Public Administration Ad Hoc Committee on Corruption in Vietnam was formed to deal with the problem. Although Roberts admonished the committee, saying "we must stop burying our heads in the sand like ostriches" when faced with corruption and smuggling, and begged, "Above all, don't make this a classified subject and thereby bury it," the U.S. Embassy decided to do just that. Embassy officials whom Roberts described as advocates of "noble kid glove concept of hearts and minds" had decided not to interfere with smuggling or large-scale corruption because of "pressures which are too well known to require enumeration."

Frustrated at the Embassy's failure to take action, an unknown member of U.S. customs leaked some of Roberts' reports on corruption to a Senate subcommitte chaired by Sen. Albert Gruening of Alaska. When Senator Gruening declared in February 1968 that the Saigon government was "so corrupt and graft-ridden that it cannot begin to command the loyalty and respect of its citizens, U.S. officials in Saigon defended the Thieu-Ky regime by saying that "it had not been proved that South Vietnam's leaders are guilty of receiving "rake-offs." A month later Senator Gruening released evidence of Ky's 1961-1962 opium trafficking, but the U.S. Embassy protected Ky from further investigations by issuing a flat denial of the senator's charges.

While these sensational exposes of smuggling at Tan Son Nhut's civilian terminal grabbed the headlines, only a few hundred yards down the runway VNAF C-47 military transports loaded with Laotian opium were landing unnoticed. Ky did not relinquish command of the air force until November 1967, and even then he continued to make all of the important promotions and assignments through a network of loyal officers who still regarded him as the real commander. Both as premier and vice-president, Air Vice-Marshal Ky refused the various official residences offered him and instead used $200,000 of government money to build a modern, air-conditioned mansion right in the middle of Tan Son Nhut Air Base. The "vice-presidential palace," a pastel-colored monstrosity resembling a Los Angeles condominium, is only a few steps away from Tan Son Nhut's runway, where helicopters sit on twenty-four-hour alert, and a minute down the road from the headquarters of his old unit, the First Transport Group. As might be expected, Ky's staunchest supporters were the men of the First Transport Group. Its commander, Col. Luu Kim Cuong, was considered by many informed observers to be the unofficial "acting commander" of the entire air force and a principal in the opium traffic. Since command of the First Transport Group and Tan Son Nhut Air Base were consolidated in 1964, Colonel Cuong not only had aircraft to fly from southern Laos and the Central Highlands (the major opium routes), but also controlled the air base security guards and thus could prevent any search of the C-47s.

Once it reaches Saigon safely, opium is sold to Chinese syndicates who take care of such details as refining and distribution. Loan's police used their efficient organization to "license" and shake down the thousands of illicit opium dens concentrated in the fifth, sixth, and seventh wards of Cholon and scattered evenly throughout the rest of the capital district.

Although morphine base exports to Europe had been relatively small during the Diem administration, they increased during Ky's administration as Turkey began to phase out production in 1967-1968. And according to Lt. Col. Lucien Conein, Loan profited from this change:

Loan organized the opium exports once more as a part of the system of corruption. He contacted the Corsicans and Chinese, telling them they coud begin to export Lao's opium from Saigon if they paid a fixed price to Ky's political organization.

Most of the narcotics exported from South Vietnam - whether morphine base to Europe or raw opium to other parts of Southeast Asia - were shipped from Saigon Port on ocean-going freighters. (Also, Saigon was probably a port of entry for drugs smuggled into South Vietnam from Thailand.) The director of the Saigon port authority during this period was Premier Ky's brother-in-law and close political adviser, Lt. Col. Pho Quoc Chu (Ky had divorced his French wife and married a Vietnamese). Under Lieutenant Colonel Chu's supervision all of the trained port officers were systematically purged, and in October 1967 the chief U.S. customs adviser reported that the port authority "is now a solid coterie of GVN military officers." However, compared to the fortunes that could be made from the theft of military equipment, commodities, and manufactured goods, opium was probably not that important.

Loan and Ky were no doubt concerned about the critical security situation in Saigon when they took office, but their real goal in building up the police state apparatus was political power. Often they seemed to forget who their "enemy" was supposed to be, and utilized much of their police-intelligence network to attack rival political and military factions. Aside from his summary execution of an NLF suspect in front of U.S. television cameras during the 1968 Tet offensive, General Loan is probably best known to the world for his unique method of breaking up legislative logjams during the 1967 election campaign. A member of the Constituent Assembly who proposed a law that would have excluded Ky from the upcoming elections was murdered. His widow publicly accused General Loan of having ordered the assassination. When the assembly balked at approving the Thieu-Ky slate unless they complied with the election law, General Loan marched into the balcony of the assembly chamber with two armed guards, and the opposition evaporated. When the assembly hesitated at validating the fraudulent tactics the Thieu-Ky slate had used to gain their victory in the September elections, General Loan and his gunmen stormed into the balcony, and once again the representatives saw the error of their ways.

Under General Loan's supervision, the Ky machine systematically reorganized the network of kickbacks on the opium traffic and built up an organization many observers fell was even more comprehensive than Nhu's clandestine apparatus. Nhu had depended on the Corsican syndicates to manage most of the opium smuggling between Laos and Saigon, but their charter airlines were evicted from Laos in early 1965. This forced the Ky apparatus to become much more directly involved in actual smuggling than Nhu's secret police had ever been. Through personal contacts in Laos, bulk quantities of refined and raw opium were shipped to airports in southern Laos, where they were picked up and smuggled into South Vietnam by the air force transport wing. The Vietnamese Customs Service was also controlled by the Ky machine, and subtantial quantities of opium were flown directly into Saigon on regular commercial air flights from Laos. Once the opium reached the capital it was distributed to smoking dens throughout the city that were protected by General Loan's police force. Finally, through its control over the Saigon port authority, the Ky apparatus was able to derive considerable revenues by taxing Corsican morphine exports to Europe and Chinese opium and morphine shipments to Hong Kong. Despite the growing importance of morphine exports, Ky's machine was still largely concerned with its own domestic opium market. The GI heroin epidemic was still five years in the future.

Thieu Takes Command

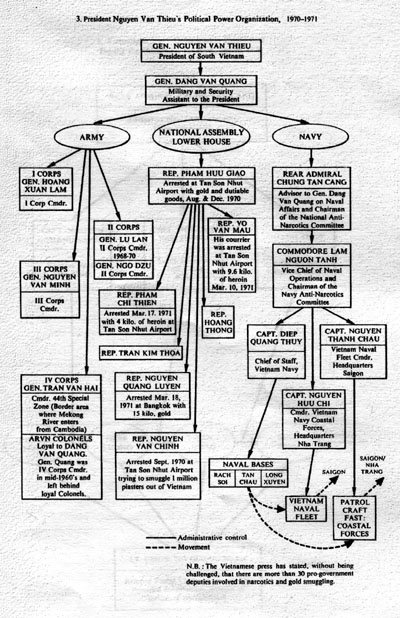

In the wake of Air Vice-Marshal Ky's precipitous political decline, ranking military officers responsible to President Thieu appear to have emerged as the dominant narcotics traffickers in South Vietnam. Like his predecessors, President Diem and Premier Ky, President Thieu has studiously avoided involving himself personally in political corruption. However, his power broker, presidential intelligence adviser Gen. Dang Van Quang, is heavily involved in these unsavory activities. Working through high-ranking army and navy officers personally loyal to himself or President Thieu, General Quang has built up a formidable power base. Although General Quang's international network appears to be weaker than Ky's, General Quang does control the Vietnamese navy, which houses an elaborate smuggling organization that imports large quantities of narcotics either by protecting Chinese maritime smugglers or by actually using Vietnamese naval vessels. Ky's influence among high-ranking army officers has weakened considerably, and control over the army has now shifted to General Quang. The army now manages most of the distribution and sale of heroin to American GIs. In addition, a bloc of pro-Thieu deputies in the lower house of the National Assembly have been publicly exposed as being actively engaged in heroin smuggling, but they appear to operate somewhat more independently of General Quang than the army and navy.

On the July 15, 1971, edition of the NBC Nightly News, the network's Saigon correspondent, Phil Brady, told a nationwide viewing audience that both President Thieu and Vice-President Ky were financing their election campaigns from the narcotics traffic. Brady quoted "extremely reliable sources" as saying that President Thieu's chief intelligence adviser, Gen. Dang Van Quang, was "the biggest pusher" in South Vietnam. Although Thieu's press secretary issued a flat denial and accused Brady of "spreading falsehoods and slanders against leaders in the government, thereby providing help and comfort to the Communist enemy," he did not try to defend General Quang, renowned as one of the most dihonest generals in South Vietnam when he was commander of IV Corps in the Mekong Delta.

In July 1969 Time magazine's Saigon correspondent cabled the New York office this report on Gen. Quang's activities in IV Corps:

While there he reportedly made millions by selling offices and taking a rake off on rice production. There was the famous incident, described in past corruption files, when Col. Nguyen Van Minh was being invested as 21st Division commander. He had been Quang's deputy corps commander. At the ceremony the wife of the outgoing commander stood up and shouted to the assembled that Minh had paid Quang 2 million piasters ($7,300) for the position...Quang was finally removed from Four Corps at the insistence of the Americans.

General Quang was transferred to Saigon in late 1966 and became minister of planning and development, a face-saving sinecure. Soon after President Thieu's election in September 1967, he was appointed special assistant for military and security affairs. General Quang quickly emerged as President Thieu's power broker, and now does the same kind of illicit fund raising for Thieu's political machine that the heavy-handed General Loan did for Ky's.

President Thieu, however, is much less sure of Quang than Premier Ky had been of General Loan. Loan had enjoyd Ky's absolute confidence and was entrusted with almost unlimited personal power. Thieu, on the other hand, took care to build up competing centers of power inside his political machine to keep General Quang from gaining too much power. As a result, Quang has never had the same control over the various pro-Thieu mini-factions as Loan had over Ky's apparatus. As the Ky apparatus's control over Saigon's rackets weakened after June 1968, various pro-Thieu factions moved in. In the political shift, General Quang gained control of the special forces, the navy and the army, but one of the pro-Thieu cliques, that headed by Gen. Tran Thien Khiem, gained enough power so that it gradually emerged as an independent faction itself. However, at the very beginning most of the power and influence gained from Ky's downfall seemed to be securely lodged in the Thieu camp under General Quang's supervision.

There is evidence that one of the first new groups which began smuggling opium into South Vietnam was the Vietnamese special forces contingents operating in southern Laos. In August 1971 The New York Times reported that many of the aircraft flying narcotics into South Vietnam "are connected with secret South Vietnamese special forces operating along the Ho Chi Minh Trail network in Laos." Based in Kontum Province, north of Pleiku, the special forces "assault task force" has a small fleet of helicopters, transports, and light aircraft that fly into southern Laos on regular sabotage and long-range reconnaissance forays. Some special forces officers claim that the commander of this unit was transferred to another post in mid 1971 because his extensive involvement in the narcotics traffic risked exposure.

But clandestine forays were a relatively inefficient method of smuggling, and it appears that General Quang's apparatus did not become heavily involved in the narcotics trade until the Cambodian invasion of May 1970. For the first time in years the Vietnamese army operated inside Cambodian; Vietnamese troops guarded key Cambodian communication routes, the army assigned liaison officers to Phnom Penh, and intelligence officers were allowed to work inside the former neutralist kindom. More importantly, the Vietnamese navy began permanent patrols along the Cambodian stretches of the Mekong and set up bases in Phnom Penh.

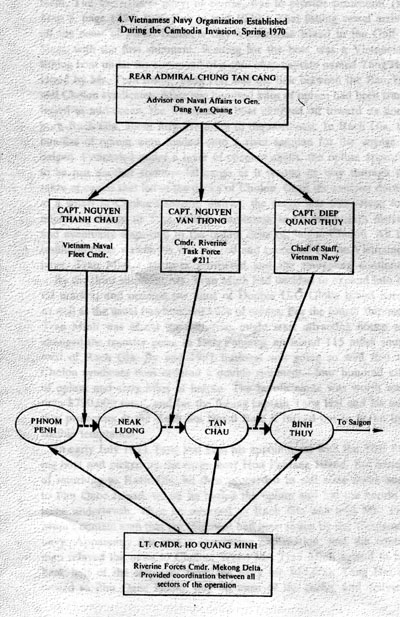

The Vietnamese Navy: Up the Creek

The Vietnamese navy utiltized the Cambodian invasion to expand its role in the narcotics traffic, opening up a new pipeline that had previously been inaccessible. On May 9 an armada of 110 Vietnamese and 30 American river craft headed by the naval fleet commander, Capt. Nguyen Thanh Chau, crossed the border into Cambodia, speeding up the Mekong in a dramatic V-shaped formation. The next day the commander of Riverine Task Force 211, Capt. Nguyen Van Thong landed several hundred Vietnamese twenty miles upriver at Neak Luong, a vital ferry crossing on Route 1 linking Phnom Penh with Saigon. Leaving their American advisers behind here, the Vietnamese arrived at Phnom Penh on May 11, and on May 12 reached Kompong Cham, seventy miles north of the Cambodian capital, thus totally clearing the waterway for their use. Hailed as a tactical coup and a great "military humanitarian fleet" by navy publicists, the armada also had, according to sources inside the Vietnamese navy, the dubious distinction of smuggling vast quantities of opium and heroin into South Vietnam.

An associate of General Quang's, former navy commander Rear Admiral Chung Tan Cang, rose to prominence during the Cambodian invasion. Admiral Cang had been a good friend of President Thieu's since their student days together at Saigon's Merchant Marine Academy (class of '47). When Admiral Cang was removed from command of the navy in 1965, after being charged with selling badly needed flood relief supplies on the black market instead of delivering them to the starving refugees, Thieu had intervened to prevent him from being prosecuted and had him appointed to a face-saving sinecure.

Sources inside the Vietnamese navy say that a smuggling network which shipped heroin and opium from Cambodia back to South Vietnam was set up among high-ranking naval officers shortly after the Vietnamese navy docked at Phnom Penh. The shipments were passed from protector to protector until they reached Saigon: the first relay was from Phnom Penh to Neak Luong; the next, from Neak Luong to TanChau, just inside South Vietnam; the next, from Tan Chau to Binh Thuy. From there the narcotics were shipped to Saigon on a variety of naval and civilian vessels.

As the Cambodian military operation drew to a close in the middle of 1970, the navy's smuggling organization (which had been bringing limited quantities of gold, opium and dutiable goods into Vietnam since 1968) expanded.

Commodore Lam Nguon Tanh was appointed vice-chief of naval operations in August of 1970. Also a member of Thieu's class at the Merchant Marine Academy (class of '47) Commodore Tanh had been abruptly removed from his post as navy chief of staff in 1966. Sources inside the navy allege that high-ranking naval officals used three of the Medong Delta naval bases under Commodore Tanh's command - Rach Soi, Long Xuyen, and Tan Chau - as drop points for narcotics smuggled into Vietnam on Thai fishing boats or Cambodian river sampans. From these three bases, the narcotics were smuglled to Saigon on naval weeks or on "swift basts" (officially known as PCFs, or Patrol Craft Fast). When, as often happened, the narcotics were shipped to Saigon on ordinary civilian sampans or fishing junks, their movements were protected by these navy units.

Although these precautions should have proved adequate, events and decisions beyond General Quang's control nearly resulted in a humiliating public expose. On July 25, 1971, Vietnamese narcotics police, assisted by Thai and American agents, broke up a major chiu chau Chinese syndicate based in Cholon, arrested 60 drug trafficers, and made one of the largest narcotics seizures in Vietnam's recent history - 51 kilos of heroin and 334 kilos of opium. Hailed in the press as a great victory for the Thieu governmnent's war on drugs, these raids were actually something of a major embarrassment, since they partially exposed the navy smuggling ring.

The Vietnamese Army: Marketing the Product

While the Vietnamese navy is involved in drug importing, pro-Thieu elements of the Vietnamese army (ARVN) manage much of the distribution and sale of heroin to GIs inside South Vietnam. But rather than risking exposure by having their own officers handle the more vulnerable aspects of the operation, highranking ARVN commanders generally prefer to work with Cholon's Chinese syndicates. Thus, once bulk heroin shipments are smuggled into the country either by the military itself or by Chinese protected by the military-they are usually turned over to Cholon syndicates for packaging and shipment. From Cholon, Chinese and Vietnamese couriers fan out across the country, delivering multikilo lots of heroin to military commanders from the Delta to the DMZ. In three of the four military zones, the local distribution is supervised and protected by high-ranking army officers. In the Mekong Delta (IV Corps) local sales are controlled by colonels loyal to General Quang; in the south central part of the country (II Corps) heroin distribution has become a subject of controversy between two feuding generals loyal to President Thieu, the former II Corps commander Gen. Lu Lan and the present commander Gen. Ngo Dzu; and in northernmost I Corps the traffic is directed by deputies of the corps commander. In June 1971 the chief U.S. police adviser filed a memorandum on Gen. Ngo Dzu's involvement in the heroin trade that describes the relationship between Cholon's Chinese racketeers and Vietnamese generals:

"HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES MILITARY COMMAND, VIETNAM APO SAN FRANCISCO 96222 Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, CORDS MACCORDS-PS 10 June 1971

MEMORANDUM FOR RECORD SUBJECT: Alleged Trafficking in Heroin (U)

1. A confidential source has advised this Directorate that the father of General Dzu, MR 2 Commanding General, is trafficking in heroin with Mr. Chanh, an ethnic Chinese from Cholon. (Other identification not available.)

2. General Dzu's father lives in Qui Nhon. Mr. Chanh makes regular trips to Qui Nhon from Saigon usually via Air Vietnam, but sometimes by General Dzu's private aircraft. Mr. Chanh either travels to Qui Nhon alone, or with other ethnic Chinese. Upon his arrival at the Qui Nhon Airport he is met by an escort normally composed of MSS and/or QC's [military police]; Mr. Chanh is then allegedly escorted to General Dzu's father, where he turns over kilogram quantities of heroin for U.S. currency. Mr. Chanh usually spends several days in Qui Nhon, and stays at the Hoa Binh Hotel, Gia Long Street, Qui Nhon. When Chanh returns to Saigon he is allegedly also given an escort from TSN Airport.

3. The National Police in Qui Nhon especially those police assigned to the airport, are reportedly aware of *the activity between General Dzu's father and Mr. Chanh, but are afraid to either report or investigate these alleged violations fearing that they will only be made the scapegoat should they act.

4. Mr. Chanh (AKA: Red Nose) is an ethnic Chinese from Cholon about 40 years of age,

[signed] Michael G. McCann, Director Public Safety Directorate CORDS

After bulk shipments of heroin have been delivered to cities or ARVN bases near U.S. installations it is sold to GIs through a network of civilian pushers (barracks' maids, street vendors, pimps, and street urchins) or by low-ranking ARVN officers. In Saigon and surrounding 11 Corps most of the heroin marketing is managed by ordinary civilian networks, but as GI addicts move away from the capital to the isolated firebases along the Laotian border and the DMZ, the ARVN pushers become more and more predominant. "How do we get the stuff?" said one GI stationed at a desolate firebase near the DMZ, "just go over to the fence and rap with an ARVN. If he's got it you can make a purchase .

Even at Long Binh, the massive U.S. army installation on the outskirts of Saigon, Vietnamese officers work as pushers. As one GI addict based at Long Binh put it, "You can always get some from an ARVN; not a Pfc., but the officers. I've gotten it from as high as Captain."

The Khiem Apparatus: All in the Family

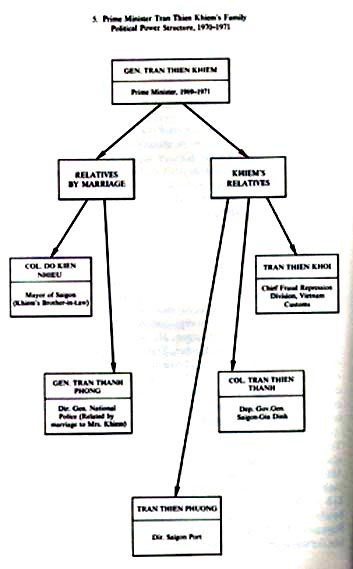

After four years of political exile in Taiwan and the United States, Khiem had returned to Vietnam in May 1968 and was appointed minister of the interior in President Thieu's administration. Khiem, probably the most fickle of Vietnam's military leaders, proceeded to build up a power base of his own, becoming prime minister in 1969. Although Khiem has a history of betraying his allies when it suits his Purposes, President Thieu had been locked in a desperate underground war with Vice-President Ky, and probably appointed Khiem because he needed his unparalleled talents as a political infighter. But first as minister of the interior and later as concurrent prime minister, Khiem appointed his relatives to lucrative offices in the civil administration and began building an increasingly independent political organization. In June 1968 he appointed his brother-in-law mayor of Saigon. He used his growing political influence to have his younger brother, Tran Thien Khoi, appointed chief of customs' Fraud Repression Division (the enforcement arm), another brother made director of Saigon Port and his cousin appointed deputy governor-general of Saigon. Following his promotion to prime minister in 1969, Khiem was able to appoint one of his wife's relatives to the position of director-general of the National Police.

One of the most important men in Khiem's apparatus was his brother, Tran Thien Khoi, chief of customs' Fraud Repression Division. Soon after U.S. customs advisers began working at Tan Son Nhut Airport in 1968, they filed detailed reports on the abysmal conditions and urged their South Vietnamese counterparts to crack down. However, as one U.S. official put it, "They were just beginning to clean it up when Khiem's brother arrived, and then it all went right out the window." Fraud Repression Chief Tran Thien Khoi relegated much of the dirty work to his deputy chief, and together the two men brought any effective enforcement work to a halt. Chief Khoi's partner was vividly described in a 1971 U.S. provost marshal's report:

He has an opium habit that costs approximately 10,000 piasters a day [$35] and visits a local opium den on a predictable schedule. He was charged with serious irregularities approximately two years ago but by payoffs and political influence, managed to have the charges dropped. When he took up his present position he was known to be nearly destitute, but is now wealthy and supporting two or three wives.

The report described Chief Khoi himself as "a principal in the opium traffic" who had sabotaged efforts to set up a narcotics squad within the Fraud Repression Division. Under Chief Khoi's inspired leadership, gold and opium smuggling at Tan Son Nhut became so blatant that in February 1971 a U.S. customs adviser reported that ". . . after three years of these meetings and countless directives being issued at all levels, the Customs operation at the airport has . . . reached a point to where the Customs personnel of Vietnam are little more than lackeys to the smugglers . . ." The report went on to describe the partnership between customs officials and a group of professional smugglers who seem to run the airport:

Actually, the Customs Officers seem extremely anxious to please these smugglers and not only escort them past the examination counters but even accompany them out to the waiting taxis. This lends an air of legitimacy to the transaction so that there could be no interference on the part of an over zealous Customs Officer or Policeman who might be new on the job and not yet know what is expected of him.

The most important smuggler at Tan Son Nhut Airport was a woman with impressive political connections:

"One of the biggest problems at the airport since the Advisors first arrived there and the subject of one of the first reports is Mrs. Chin, or Ba Chin or Chin Map which in Vietnamese is literally translated as "Fat Nine." This description fits her well as she is stout enough to be easily identified in any group.... This person heads a ring of 10 or 12 women who are present at every arrival of every aircraft from Laos and Singapore and these women are the recipients of most of the cargo that arrives on these flights as unaccompanied baggage. . . . When Mrs. Chin leaves the Customs area, she is like a mother duck with her brood as she leads the procession and is obediently followed by 8 to 10 porters who are carrying her goods to be loaded into the waiting taxis....

I recall an occasion . . . in July 1968 when an aircraft arrived from Laos.... I expressed an interest in the same type of Chinese medicine that this woman had received and already left with. One of the newer Customs officers opened up one of the packages and it was found to contain not medicine but thin strips of gold.... This incident was brought to the attention of the Director General but the Chief of Zone 2. . . . said that I was only guessing and that I could not accuse Mrs. Chin of any wrong doing. I bring this out to show that this woman is protected by every level in the GVN Customs Service."

Although almost every functionary in the customs service receives payoffs from the smugglers, U.S. customs advisers believe that Chief Khoi's job is the most financially rewarding. While most division chiefs only receive payoffs from their immediate underlings, his enforcement powers enable him to receive kickbacks from every division of the customs service. Since even so minor an official as the chief collections officer at Tan Son Nhut cargo warehouse kicked back $22,000 a month to his superiors, Chief Khoi's income must have been enormous.

In early 1971 U.S. customs advisers mounted a "strenuous effort" to have the deputy chief transferred, but Chief Khoi was extremely adept at protecting his associate. In March American officials in Vientiane learned that Rep. Pham Chi Thien would be boarding a flight for Saigon carrying four kilos of heroin and relayed the information to Saigon. When U.S. customs advisers asked the Fraud Repression Division to make the arrest (U.S. customs officials have no right to make arrests), Chief Khoi entrusted the seizure to his opium-smoking assistant. The "hero" was later decorated for this "accomplishment," and U.S. customs advisers, who were still trying to get him fired, or at least transferred, had to grit their teeth and attend a banquet in his honor.

Frustrated by months of inaction by the U.S. mission and outright duplicity from the Vietnamese, members of the U.S. customs advisory team evidently decided to take their case to the American public. Copies of the unflattering customs advisory reports quoted above were leaked to the press and became the basis of an article that appeared on the front page of The New York Times on April 22, 1971, under the headline, "Saigon Airport a Smuggler's Paradise."

The American response was immediate. Washington dispatched more customs advisers for duty at Tan Son Nhut, and the U.S. Embassy finally demanded action from the Thieu regime. Initially, however, the Saigon government was cool to the Embassy's demands for a cleanup of the customs' Fraud Repression Division. It was not until the smuggling issue became a political football between the Khiem and Thieu factions that the Vietnamese showed any interest in dealing with the problem.

Alfred W. McCoy (1973)

Harper Colophon Books

Courtesy of Adam Sadowski